As you’re likely aware, sleep is mediated by a number of factors, including metabolism, temperature and stress. The most powerful driver of sleep, however, is the sleep-wake circadian rhythm. Within human beings, this 24-hour cycle is largely mediated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus: a tiny brain region that receives direct input from the eyes and is highly responsive to sunlight. Among adults, this “master clock” typically triggers sleepiness around 9pm, deep sleep around 2am and wakefulness around 6am.

As many of us know, this clock goes a bit haywire during adolescence. Not just in human teens but in practically every animal ever studied - from rats to birds to fish - the circadian rhythm shifts. This is often presented in the media as “teenagers like sleeping in late, so we should start schools later”. But it’s a little more complex than that.

In humans, this shift manifests as a two-hour delay, so for teenagers, sleepiness is triggered around 11pm, deep sleep around 4am and wakefulness around 8am. Although the precise biological mechanisms for this shift are unclear, likely drivers include puberty hormones and neuronal pruning. But more interesting than the mechanistic question is the behavioural question: why would all animals change their sleep pattern during adolescence?

A prevailing theory concerns learning. Among most animals, the young are cared for by adults. But, come puberty, protection is withdrawn and adolescents must enter the competitive world of maturity. Food, mates, shelter: everything is up for grabs and juvenile creatures likely won’t be able to outcompete more experienced adults.

For this reason, it’s believed adolescents carve out a unique “social niche”, while adults (and children) are asleep and out of the picture. Theoretically, this allows them to practise and hone cooperative and competitive strategies with others on an equal footing.

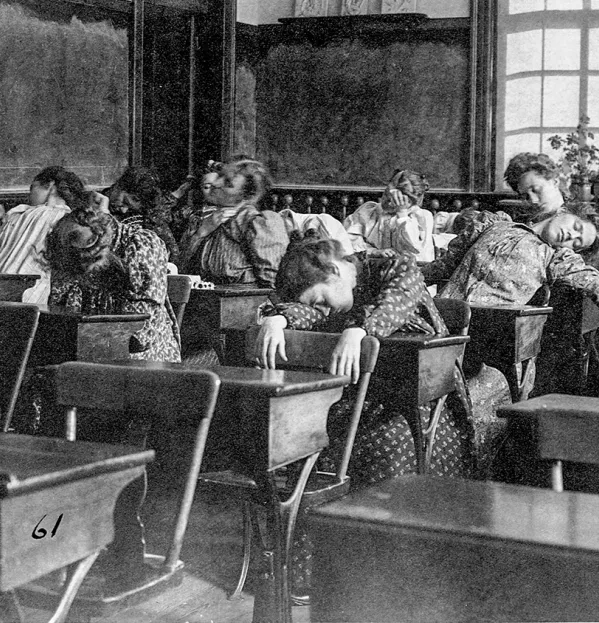

But while an adolescent sleep shift is beneficial to many animals, it can prove a hindrance to human teenagers. With the constraints of school, not only are many teenagers not fully awake for morning class but they also accumulate “sleep debt”, losing one to three hours of sleep per weeknight.

Many teenagers try to make up this debt by sleeping in at the weekend, but this only serves to push the circadian rhythm further out of sync. By the end of a term, some teens might not feel sleepy until after midnight and won’t feel awake until noon.

How can we help? The common response at the moment is: start school later. Indeed, some research suggests that later school starts can positively impact mental health and academic achievement.

Unfortunately, schools are run by adults. Asking teachers to start their day two hours later would mean many wouldn’t leave school until gone 7pm. Outside of boarding scenarios, I don’t reckon this is viable.

The key, then, lies in routine. The more teenagers have sleep (and life) routines, the better chance they have of diminishing sleep-shift impacts. Turning off technology, stopping homework and dimming lights at the same time each evening can trigger the sleep cycle. Exercise, diet and consistent pre-bed behaviours (meditation, stretching, reading) can further override the sleep shift. Avoiding naps and keeping the same wake-sleep routines on the weekend are key, too.

Things can go awry. For example, I have a nephew who recently dropped out of secondary school and is currently stuck in the “game all night, sleep all day” cycle. In these instances, a very strict sleep/wake routine, supplemented by light therapy (which aims to mimic sunlight and trick the suprachiasmatic nucleus) and pharmaceuticals may be required, though it’s best to save the heavy artillery until after all behavioural and environmental strategies have been exhausted.

Jared Cooney Horvath is a neuroscientist, educator and author. To ask our resident learning scientist a question, please email AskALearningScientist@gmail.com

This article originally appeared in the 3 April 2020 issue under the headline “Slaves to the (circadian) rhythm”