- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- How to meet the needs of EAL learners

How to meet the needs of EAL learners

The proportion of pupils who speak English as an additional language (EAL) is on the rise. In fact, the percentage has more than trebled since 1997.

Government data from the 2022-23 academic year, published in June, reveals that EAL pupils now make up around one-fifth of the primary and secondary school populations in England, and almost one-third of the children in nurseries. In some schools, the percentage will be even higher.

These rising numbers are having an effect on how teachers are choosing to teach - and the shift in practice is positive not just for EAL pupils but for everyone in school, argue experts.

Increasingly, says Katherine Solomon, head of training and resources at charity The Bell Foundation, there is recognition of the need for multilingual pedagogies, as well as a desire to place value on the first languages children bring with them to school.

“We’re used to seeing English only in the classroom, but you can see that many teachers are now encouraging pupils to use their first language when it will help them to carry out a task,” she says.

The benefits of multilingual classrooms

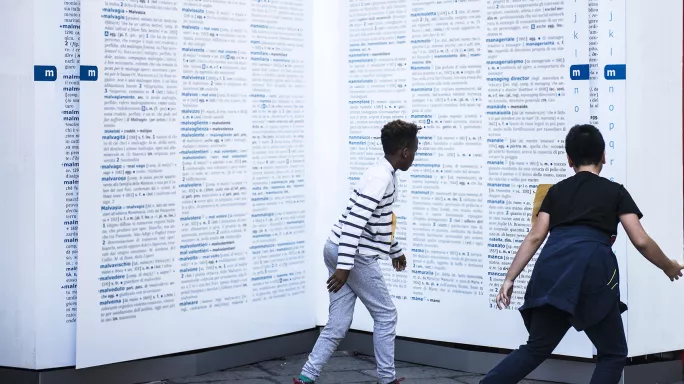

The presence of additional languages in a classroom can be beneficial for all pupils, says Victoria Murphy, professor of applied linguistics and director of the Department of Education at the University of Oxford.

“Think about the monolingual English speaker sitting next to an EAL child who is encouraged to use their first language in the classroom and share experiences of their culture,” she says.

“That experience can open monolingual speakers’ eyes to the world of languages, and pique their interest.”

If pupils do feel encouraged to pursue language study then that’s all for the best, says Graham Smith, director of the EAL Academy, an organisation that provides training to schools across the country.

“Research tells us repeatedly about the cognitive advantages of the bilingual or multilingual brain. The concept of grammar, for example, makes more sense if you can speak and think in more than one language,” he explains.

It’s not just the motivation to learn another language that’s useful, though. As Murphy points out, when teachers support multilingual children in the classroom, they often use pedagogical techniques - including incorporating more pupil talk, using visual materials and focusing more on vocabulary and how English and other languages work - that have the potential to support all children in their learning.

“It’s certainly been shown that [having EAL pupils in the classroom] isn’t a disadvantage to monolingual speakers,” says Claudine Bowyer-Crane, a psychologist and professor at the University of Sheffield.

The challenges

However, that’s not to say that the growing numbers of EAL pupils don’t also present challenges for schools.

Pupils who have low levels of English proficiency will likely struggle to access the curriculum and assessment. They may have a good knowledge base but be unable to demonstrate that in a different language.

“Our assessment system doesn’t take into account their ability if you were testing them in their own language, and so I think the biggest challenge for teachers is to bring these children up to speed in speaking and writing in English to be able to meet the needs of statutory assessments,” says Bowyer-Crane.

And it’s not just support in terms of language learning that schools need to offer, she adds, but very specific pastoral support.

What does EAL mean?

One of the key issues for schools, says Solomon, is that EAL pupils are far from being a homogenous group, which makes it more difficult to get the right provision in place.

The “EAL” label, she says, is an umbrella term that encompasses:

- Children who are second- or third-generation immigrants who speak English fluently, as well as other languages within their community.

- Children of migrants who live in the UK for a couple of years before returning to their home country.

- Refugee children or those seeking asylum who have had very disrupted schooling and may have limited literacy in both their first language and English.

The last group may also have experienced significant trauma - something that needs to be considered when thinking about how to integrate them into the classroom.

“We have to be very aware of those differences,” Solomon says.

‘For many EAL children, it’s a huge challenge to get ready to learn at the speed of the rest of the class’

Many EAL pupils, particularly those “born in Britain to bilingual families”, will need relatively low levels of support, says Robert Sharples, a lecturer in language and education at the University of Bristol.

“They will quickly become dominant in English,” he says. “They need continued support to reach their full potential but pose few challenges when schools consciously address those needs.”

Others, however, will require a lot more help - and schools will need to determine what sort of help is required, and how much of it, on an individual basis.

Identifying pupil needs

Unfortunately, there’s a lack of guidance from the Department for Education around how schools should identify and meet the needs of EAL learners - and a lack of prioritisation at policy level when it comes to support, says Bowyer-Crane.

Solomon agrees that there is currently a gap in guidance here; she highlights that provision for EAL learners is not mentioned in the Early Career Framework, for instance.

This lack of consideration comes at a time when the need for support is higher than ever.

Bowyer-Crane has worked with others on a longitudinal study for the National Institute of Economic and Social Research that looks at the impact of Covid-19 on children’s language, education and socioemotional skills. This research has found that EAL children are performing more poorly than their peers.

So, what can schools do to maximise the cultural and linguistic benefits of their multilingual communities while minimising the challenges for staff?

CORE Education Trust in the Midlands offers one innovative approach. In response to increasing numbers of EAL pupils entering its schools, the trust has established a programme called CORE Hello. It’s an intensive language learning programme, delivered to small classes of pupils with low levels of English.

Over 12 weeks, pupils learn basic language “survival skills”, are taken on trips in their local area to get acclimatised and are given pastoral and trauma support - all before going into mainstream classrooms.

“For many children who are put into mainstream classrooms when they first arrive in the UK, it’s a huge challenge for both them and their teacher in trying to get settled and ready to learn at the speed of the rest of the class,” explains Emily Preece, director of CORE Hello.

Taking part in the programme, however, gives these pupils time to adjust and an extra boost in allowing them to access the curriculum.

“It’s made a massive difference,” says Preece. “With CORE Hello we’ve found that, in a short period of time, [pupils] make progress that, in a normal school setting, may take a year or two.”

CORE Hello is staffed by three specialist EAL teachers, who also offer support and training to teachers across the trust. Although the provision is working, it clearly requires significant resource, which not all schools will have available.

Specialist support

However, there is plenty that all schools can do on a smaller scale.

Solomon suggests that the first step in improving provision should be to measure pupils’ English language proficiency. The Bell Foundation has a free assessment tool and progress tracker that can help with this.

The results of that assessment should then feed into a pupil profile, which should also include information about which languages the pupil and their family speak, as well as the pupil’s educational experience so far.

“All that information is going to give you a much more comprehensive picture of who they are,” Solomon explains.

“You need to know if there are going to be issues around literacy, or whether there will be issues around trauma.”

‘Supporting pupils and parents to live and learn in a very different world is not always easy’

This profile can form a guide for teaching and learning leads, and demonstrate where interventions should focus. It’s likely that building English language proficiency will be a core aim, and Bowyer-Crane recommends using a tried and tested language intervention, such as the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI).

“I was involved in some work that trialled NELI with EAL pupils, and we did find that some of the techniques worked,” she says.

Emphasis on vocabulary

The programme focuses on teaching children vocabulary using multi-contextual methods and also teaching them expressive language, correct grammatical structures and phonics.

While NELI is aimed at the early years foundation stage, the techniques can be used further up the school with modified materials, says Bowyer-Crane.

Murphy agrees that emphasis on vocabulary is important. Pupils need to have a good “breadth of vocabulary knowledge in order to be able to extract meaning from text”, she says, and this is something that EAL learners may fall down on compared with native English speakers.

“Again and again, we find that most EAL children are good at single-word reading, but some EAL children often struggle with comprehension, which then leads to problems with accessing the curriculum,” she explains.

When it comes to vocabulary, research shows that EAL learners may “particularly struggle with polysemy, which is where the same word has multiple meanings”, Murphy adds.

To help with this, Murphy, along with colleagues at the University of Oxford, has developed an interactive game called Word Explorer, designed to improve children’s knowledge of polysemy, among other things. The game is currently being evaluated through a randomised controlled trial and is available for free on the Applaydu app.

‘Making pupils secure is the key’

For pupils who need specialist support on the pastoral side, Bowyer-Crane recommends the Young Interpreters scheme, developed by Hampshire County Council. This involves EAL pupils supporting newcomers who share the same language as them.

The “young interpreters” are taught different strategies to clarify, explain and interpret school activities, systems and procedures to their peers.

The scheme not only helps new pupils to access the curriculum but provides them with a buddy they can relate to, and who can support them to settle into school life.

Bowyer-Crane also recommends the Schools of Sanctuary award, which guides schools through a series of activities aimed at helping them to be a welcoming environment for refugees.

This is an area that schools might need particular support with, but which can make all the difference, says Smith.

“Supporting pupils and parents to live and learn in a very different world is not always easy,” he says. “Making them feel welcome and secure is the key.”

Ultimately, putting this support in place is more than worth it, says Sharples, because “multilingualism brings benefits to both the individual and society”.

“We want EAL pupils,” he stresses, “because we need their skills and experiences.”

Clare Cook is a freelance writer

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters