- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- How to stop working memory making learning harder

How to stop working memory making learning harder

W

e’ve all experienced that moment when an important name or fact is on the tip of our tongue but we can’t quite reach it. For those few seconds while we are thinking hard, trying to find the word, we are using our working memory. Unfortunately, this is a limited cognitive resource, and it is prone to failing.

Our working memory is the mental workbench where we receive information into our short-term memory. It can be thought of like a Post-it note: useful but with very limited space. And not only is our working memory limited but also our entire architecture for remembering is sometimes not helpful to learning.

For instance, our brain has developed to find more meaning in physical events than more cerebral tasks, such as reading or listening to the teacher in the classroom. As such, we better remember emotive experiences (otherwise known as episodic memory) compared with hard thinking about tricky abstract concepts (what is termed semantic memory).

How does memory work?

This favouring can result in pupils recalling a fun science experiment but not the findings. It may even be why, years later, we can remember - often with curious vividness - a random dog wandering across a school field, whereas hours and hours of physics formulae learning is lost to the ravages of time.

Our memory capacity for experiences, images, words and ideas is also not made equal. Typically, we have a better recall for images compared with our memory for abstractions, like words or maths formulae. But we can also develop a false memory for familiar images.

More on working memory:

- How to help children with poor working memory

- Why we need to think about working memory differently

- Tips to improve pupils’ working memory

For instance, when presented with a close-up picture in an experiment, we can remember more of the actual scene than was present. Why does this happen? Our brain knows that memory can be fragmentary, so it gets around this limitation by creatively filling in these gaps with what psychologists call boundary extension (or the boundary extension illusion). These creative additions to help us make sense of the world are broadly helpful, but in the classroom, they can lead to misunderstanding and overconfidence, as well as learning failures.

But for the purposes of this article, let’s focus on the challenges of working memory and, specifically, how to mitigate them.

Working memory and schools

Depending on the nature of what is being learned, our working memory can handle between something like four and seven bits of information before it is forgotten or stored, depending upon factors such as whether the material is familiar. We may have a memory for seven compelling images but struggle with a single multi-step maths equation that is abstract, dull or just plain difficult.

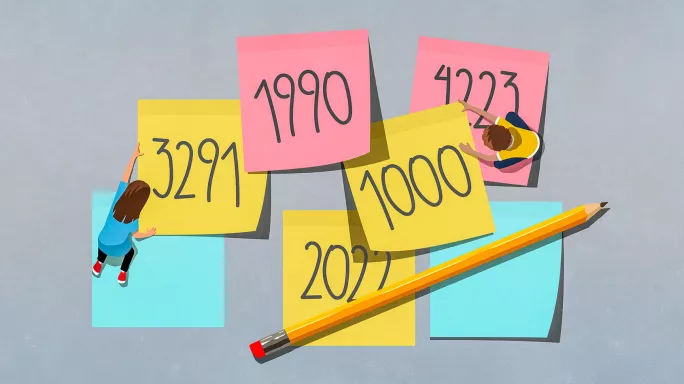

A common example to show our working memory processing in simple terms is getting to grips with remembering number strings. Look at this number sequence for around 20 seconds. Then look away and try to remember as many numbers from the sequence as you can:

32911990202210004223

How did you do?

Memory tricks

If you remembered more than nine digits, then well done. You are already outdoing the typical limits of your working memory.

Fewer than nine? Well, blame your working memory.

If you reached something like double figures, you likely applied a clever memory strategy or two to help you do the job. Well done for being both knowledgeable and strategic.

Perhaps the most popular strategy for processing number strings is chunking. This describes how we cluster together larger sequences of information, such as numbers, into more manageable and memorable chunks.

For example, you could chunk the above number sequence in the following ways:

3291 = Average marathon: 3 hours, 29 minutes and 1 second

1990 = Italia ’90 football World Cup

2022 = Two years ago

1000 = A millennia

4223 = Slow marathon: 4 hours, 22 minutes and 3 seconds.

Suddenly, armed with a relatively simple strategy, most people can spend a few minutes and begin to remember substantial number strings.

Tips for working memory

So with some instruction, the limits of our working memory can be outmanoeuvred.

In research by academics seeking to understand expertise, it was found that students could be trained to go from remembering seven digits to near-enough a record-setting 70 digits.

So can we simply stretch out our working memory to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the entirety of the school curriculum?

Alas, when memory experts trained on remembering number strings attempted to replicate their success with strings of letters, the switch in content proved problematic. The general approach to chunking and connecting information in more manageable packages is a useful principle for remembering, but strategies prove persistently subject-specific.

For instance, remembering lines from a poem requires subtly different chunking from number strings or physics equations. Applying the right memory strategy is therefore nuanced and our novice pupils require support and explicit instruction on a subject-specific basis.

Remembering text quotes

Consider the working memory demand of this classic quotation from Macbeth:

“Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

With this speech, pupils’ working memory is likely to be working overtime. They are mentally juggling whether the brief candle is real or imagined, before then grappling with the lengthy extended metaphor of life being like a gloomy stage actor.

They are also attempting to decode the words from the page and understand unfamiliar vocabulary, like “struts” and “frets”, all while aiming to infer meaning from the lengthy clause-laden sentence.

Sentence length matters to working memory limits, too. Sentences of 11 words are considered easy to read, but those of 21 words are viewed as difficult, and then those of 29 words or longer are deemed very difficult. So how tricky are 35-word lines from Shakespeare? Make your own judgement.

Impact on performance

Struggling with working memory is related to pupils’ ability to plan, to problem-solve and to sustain their attention. Professor Susan Gathercole and colleagues found that 41 per cent of children who achieved below-average scores on national English tests at age 6 and 7 had working memory scores in the deficit range, as did 52 per cent of children who achieved the same low levels in national mathematics tests at this age.

Faced with a multi-step word problem in mathematics, pupils can quickly get stuck, fail to hold their calculations in mind, and, if it goes wrong too frequently, simply give up trying.

Even seemingly accessible instructions - such as “Put away your reading books, take out your spelling book, write the date at the top of a new page, and then turn to face the front” - can prove too taxing for young pupils to follow successfully. They are not able to chunk down the instructions because their working memory is overwhelmed by the excess information.

It is perhaps no surprise that a lack of sleep can exacerbate already narrow working memory limits. That feeling of it being harder to think and concentrate when tired is all too common, particularly for teenagers whose body clock is shifting and whose decision-making isn’t always forward-thinking.

It isn’t too difficult for a teacher to imagine the scene where some of their pupils are tired, some are hungry, some are distracted and some are finding the topic particularly tricky, and as a result, the class are struggling to remember and to learn.

Strategies for teachers

There is no easy, quick fix to expand our working memory beyond years of learning and accruing vast stores of knowledge and skill. That said, when teachers and pupils know the narrow limits of working memory - and what they can do to learn more efficiently with those limits in mind - they can learn with greater degrees of success.

Here are some techniques you can use to mitigate working memory challenges with pupils.

1. Failure can breed success

It can be valuable to help pupils understand that failing and reaching an impasse with a difficult task can potentially benefit their memory for learning. Professor Roger Schank coined the failure-driven memory theory to describe how failure can often be productive for learning.

He describes how when we learn, we create memory scripts for solving problems or undertaking tasks. The experience of failure can generate enough interest in pupils to pursue solutions to their learning failures. If they are subsequently successful, it helps to create a new, more memorable script to tackle similar challenges in the future.

In short, the experience of struggling can stick in our pupils’ longer-term memory in a productive fashion, if the errors or failures are clearly addressed.

2. Harness episodic memory

Teachers can also draw upon the power of pupils’ episodic memory. As pupils’ natural proclivity is to remember experiences, and new learning that is tied to emotional experiences, teachers can be strategic about planning such episodes into the school curriculum.

What better way to learn about capital cities or coastal erosion than by visiting a place on a well-planned school trip?

But you don’t have to leave the classroom to invoke episodic memory. You can wed a complex topic to powerful storytelling that consolidates understanding. For instance, the striking personal stories of Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale can both illuminate the history of medicine and build emotive connections when learning the history topic.

3. Shrink the challenge

Another key to helping pupils navigate the narrow parameters of working memory is “shrinking the challenge”. Take a Year 4 class who are undertaking a narrative writing task. Writing is one of the most demanding activities known to mankind and is always likely to overload pupils. They must create imagined worlds, compose sentences, consider spelling, write in coherent paragraphs, select vocabulary, edit, revise and more…pretty much all at once.

We can shrink the challenge and create stepped tasks for each stage of the writing process.

Let’s isolate just one important stage: revising to improve your draft. We can start by shrinking the editing task with an approach such as “best and better”. Put simply, this approach asks pupils to identify their best sentence (explaining why), before asking them to select a sentence they need to make better. With a shrunken focus on only two sentences, thereby circumventing working memory limits, we can better explore, discuss and model revising writing.

4. Build a memory palace

Another tactic comes from ancient Greece. Back then, memory feats were being achieved by the method of loci (or the memory palace). Remember we have a better recall for images over abstractions like the written word? Well, this 2,500-year-old learning strategy exercises this strength. A pupil memorises the layout of a familiar building, such as their home or school. To remember a set of items (these can indicate concepts or facts), they mentally walk through the building and allocate items to remember in specific positions. The journey gets rehearsed over and over, with the aim of meaningfully connecting the items.

For example, if you are trying to remember some of the factors that led to the outbreak of the Second World War, you could set your location as home. Perhaps Neville Chamberlain opens the front door for you, representing the policy of appeasement. In the hallway, a new chandelier hangs, evoking the Hall of Mirrors at the Treaty of Versailles. At the heart of the chandelier, four candles stand, representing the leaders of the victorious Western Nations…and so on.

The verbal and visual rehearsal at the heart of the success of this memory strategy draws upon our spatial and visual memory, but it is also anchored in our prior knowledge of familiar places. In short, potentially disconnected facts are made more meaningful in an elaborate series of connected chunks.

Creating metamemory

So the limits of working memory cannot be wholly erased, but teachers can mitigate them significantly. What is clear is that establishing metamemory - our pupils understanding the function and foibles of their own memory - must go beyond a couple of clever assemblies. Careful strategy instruction and high-quality explicit teaching are also necessities.

Many of the strategies to push learning through the eye of the working memory needle are familiar to teachers, and some are ancient and well-established. Let’s return to those, keeping them on the tip of our tongue when teaching and guiding pupils’ learning from failure to success.

Alex Quigley, a former teacher, is the national content and engagement manager at the Education Endowment Foundation. This article is an extract from his new book Why Learning Fails (And What to Do About It), published by Routledge.

For the latest research, pedagogy and practical classroom advice delivered directly to your inbox every week, sign up to our Teaching Essentials newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.