- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Howard Gardner: Multiple intelligences, learning styles and me

Howard Gardner: Multiple intelligences, learning styles and me

Howard Gardner is tired of talking about multiple intelligences.

It’s the theory that he is best known for in education circles, and one that many connect to the theory of “learning styles” - the now widely debunked idea that individuals are better suited to a particular style of learning.

But Gardner himself is keen to move on and to distance his work further from discussions about learning styles.

“I developed the multiple intelligences theory over 40 years ago, and I’ve had a lifetime of work since then,” he says. “I don’t want it just to say ‘MI theory’ on my gravestone.”

Gardner is a developmental psychologist, and the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs research professor of cognition and education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. And after decades of working in education research, he has plenty of insights beyond his ideas about multiple intelligences.

Tes sat down with him to revisit his past work, and to learn about how his new theory of the synthesising mind could translate to the classroom.

Tes: Many teachers associate your name with the theory of multiple intelligences. Can you explain how you define that theory?

Howard Gardner: The theory of multiple intelligences was developed in the late 70s and is a critique of the idea - put forward by British researchers Sir Cyril Burt and Hans Eysenck - that intelligence is a single thing, measurable by an IQ test.

Over five years, I strongly challenged this claim, drawing on many disciplines including genetics, neuroscience and anthropology, and put forward a pluralistic theory of intellect called the multiple intelligences (MI) theory.

The idea is very simple. If you believe in a single intelligence, it means you have one computer in your head. If it works well, you’re good at everything. If it works averagely, you’re average at everything. If it doesn’t work well, you won’t do well at anything.

Any teacher who has seen hundreds of kids knows that’s nonsense. If a child is good at music, it doesn’t mean they’ll be good at chess, cricket, or composition, too.

My research says there are eight different types of “computer”, or intelligences (see box) in our brains. One computer may work well, say the linguistic one, but that doesn’t mean the musical or spatial computers also work well.

MI is often associated with the learning styles theory, which suggests children are either auditory, visual or kinesthetic learners. How do you feel about that association?

Learning styles is not something I believe in, and I’ve spent a lot of time, alas unsuccessfully, trying to distinguish MI from learning styles.

The confusion between them is exhibited by educators all over the world. They’re looking for a quick explanation because they’re busy, and aren’t particularly research oriented. They say, “MI and learning styles both say kids are different”. End of discussion.

What is the difference between the two?

MI theory is based on empirical research, conducted over five years in a number of disciplines. I’m constantly reading neurological, genetic, psychological and anthropological literature and updating the theory, as seems appropriate.

Learning styles, however, is an intuition people have; some kids learn better when things are presented to them in a visual way, or an auditory way.

But it’s nonsense from the point of view of MI theory; typically when people call kids “visual”, they ignore the fact that reading is visual, and often the kids they call “visual learners” are not good readers.

Then, the auditory style is about music, as well as speaking - but there’s no particular connection between how musical you are and how well you speak and understand language.

Learning style theory doesn’t make intellectual sense. MI theory does, and has very real implications in the classroom.

What are those implications?

There are two important educational implications: individualisation and pluralisation.

Let’s start with individualisation. This, essentially, is one-on-one tutoring. When a tutor understands each of their students, and knows what their intelligences are, the tutor can personally give them exactly what they need in terms of teaching.

In the past, only wealthy people have been able to afford a tutor. However, technology has given teachers, and parents, tremendous possibilities for individualisation.

Once we discover what interests students, what they focus on, what grabs and holds their attention, and what catalyses progress, we can use technology to deliver content in a way that suits their intelligences. One child might read the book, while another watches the play based on the book on YouTube, for example. That’s individualisation.

And what about pluralisation?

Pluralisation is a much deeper idea. I’m very interested in what we want children to learn. In the United States, we attempt to teach students way too much. A week on the industrial revolution, a week on the French Revolution, a week on the Russian Revolution. It just about guarantees superficial learning.

Pluralisation means deciding what’s really important and then spending a lot of time on those seminal topics. When you spend a lot of time on those topics, you can approach them through different intelligences.

For example, if you take something like Darwinian evolution, facets of it can be taught through language, poetry, logic and mathematics, graphs and mapping, drama and dance, and so on. I detail this approach in my book, The Disciplined Mind.

If you approach an important topic in lots of different ways, you’re going to reach more kids and foster deeper understandings.

So for me, the educational implications of MI theory are teaching each person in the way he or she can learn the best.

How can teachers tell which kind of intelligence each child has?

There is no simple MI test, but there are ways of finding out.

Before I get into that, I want to say this: if a child is happy, leave them be. Say a prayer of thanks that they are doing reasonably well in school and aren’t bored or anxious. In parts of the West with which I am familiar, we spend way too much time and money trying to study and psychoanalyse children.

However, if you do want to know your child’s intellectual profiles, the best thing to do is to repeatedly visit a children’s museum.

Nobody “fails” at the museum; there are lots of things to do.

Observe the children and see what interests them, and what they go back to. If the child keeps going to the water game, or the number game, or always picks up a musical instrument, and then explores it in various ways, it’s a sign the child has promise with a particular intelligence.

Can a child show promise in more than one intelligence?

Look, life is not fair. Some children will have strengths in several, while others will have fewer areas of strength.

People have a very jagged profile, and that can change, depending on people’s exposure to opportunities, where they live, the context they are brought up in, their own motivation, the skills of teachers or mentors, and the rewards and penalties in the society.

If I lived in a culture where music was not particularly valued, for example, my musical talent would be irrelevant. Or, if I lived in Finland or Hungary, where just about everybody learns to sing, I might not stand out.

People can also practice, and get better at things.

Some people have criticised the MI theory by saying that it lacks empirical evidence. What is your response to that?

It’s essential to distinguish between empirical evidence and experimental evidence. MI theory is based entirely on empirical evidence from a range of disciplines - as documented in my original book, which was published in 1983, with copious footnotes and updated in subsequent editions, and hundreds of blogs.

MI is not an experimental theory. You can’t do one experiment, or even a dozen experiments, and say, “Ah the theory is right” or “Ah, the theory is wrong and here’s how to fix it.” It’s a synthesis of lots of empirical evidence from a range of sciences and social sciences.

I can’t help but wonder whether those who raise this objection have ever read my book, or even encountered the response I offer.

You’ve moved on from researching multiple intelligences in recent years. What are you most interested in at the moment?

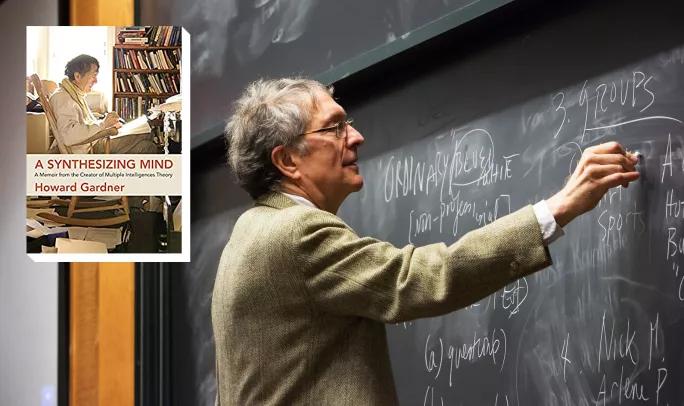

I’ve become obsessed with the idea of the synthesising mind. I believe it is the most important thing teachers could teach their students.

This theory starts with my own introspections. When I wrote a memoir a few years ago, I held a mirror up to my mind and, initially, I thought there wasn’t anything interesting about my brain. But when I looked deeper, I realised I have a synthesising mind.

What is a synthesising mind?

Put simply, it’s a mind that can survey experiences and data across a wide range of disciplines, sources of information and perspectives, and then assemble them in a useful way.

I used this ability for decades without thinking too deeply about it. I spent years writing textbooks for students: a classic example of synthesising.

And then, about 25 years ago, Murray Gell-Mann, a brilliant Nobel Prize winner in Physics, said to me: “Howard, in the 21st century, the synthesising mind is going to be the most important thing.”

I was struck by what a profound statement it was.

Why did it feel so profound?

If we want to access information, we can Google it. We no longer need to have a good memory for words and dates. But being able to put information together, in a way that makes sense to you and also to other people is a critical skill for today’s world.

When you’re working on a project - trying to understand something, explain something, sell something, create a company, you name it - if you don’t have a synthesising mind, you have to find somebody else who does. Or you have to rely on an algorithm that may or may not be designed to do what you want to do in a way you are comfortable with.

What does that mean for how teachers teach?

Teachers should increasingly focus on nurturing a synthesising mind in their students.

Good educators need to give less attention to memorising things like times tables and spelling, and devote more attention to helping students become synthesisers.

Societies that value synthesising will be ahead of the game. There is so much that artificial intelligence can do quicker and better; synthesising may be the last thing the human mind can still do better than a machine.

And even if we have machines that synthesise deftly, they may not synthesise with our purposes or goal or values in mind.

We’re obviously not going to see schools dropping times tables completely any time soon. So, what could a focus on synthesising look like in practice?

For example, let’s say everybody reads a book and then writes a book report.

Let’s compare three of those reports, and see which students have pulled knowledge together and are presenting a new insight, and which ones are simply regurgitating what the author said and pronouncing whether it’s good or bad.

Teachers need to value synthesising and put it at the heart of their teaching. The good thing is, the bar is currently so low, it’s easy to get better. Very few teachers or education scholars have thought seriously and systematically about this or taught this before.

In fact, the educational theorist Benjamin Bloom used to value synthesising, but ultimately dropped it from his Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.

Can you teach students to get better at synthesising?

Yes. There are some clear stages or steps to enhance synthesising ability.

Let me give an example: to begin with, students should conceptualise the problem, the project, the enterprise, and identify a starting point, or points.

Then, they should envision the shape of the likely end product - more than one possibility is likely here - and search for good, and not-so-good, models of the final product.

Next, they need to reflect on the means and media at one’s disposal: here they should draw on their own favoured intelligences and the subjects and disciplines with which they have some familiarity.

- Michael Young: What we’ve got wrong about knowledge and curriculum

- Dylan Wiliam’s vision for fair and accurate assessment

They should then activate these means and these media, and identify, collect and evaluate relevant information, data and ideas - while discarding those that seem inappropriate.

Afterwards, students should create drafts, sketches and portfolios in symbol systems with which they are comfortable, for example, charts, grids, tables, metaphors, narratives, formulas, diagrams or equations. These elements - a pivotal stage en route to an effective synthesis - should be arranged in different configurations, compared with one another, and students should then produce a first draft.

Feedback should then be gathered from those who will consume the end product (you as the teacher), and then students should create a second draft.

The second draft should be submitted for feedback from other experts, perhaps other teachers or their peers, and this feedback should then inform the final draft.

Of course, this is for a significant synthesis like a final course paper. More modest ambitions are appropriate for interim course assignments.

How does that fit into a subject-based curriculum? When should synthesising be used?

It can be used in every subject.

In politics, citizenship or history, for example, if a world leader makes a speech, students could synthesise what they are saying beyond the words they speak. When they say X, what do they really mean? How are they referring to popular culture, history and geography? What are they saying about their predecessors? Students should unpack what’s on the surface and ask what’s really underneath; that would be a synthesis.

Let’s take two subjects that people wouldn’t usually have together: history and music. We could ask students: how was Beethoven influenced in a positive and a negative way by Bach or Mozart? How were The Beatles influenced in a positive or negative way by Elvis Presley?

Or if you look at Elizabeth the first and Elizabeth the second. They’ve got the same name, and they were both influential monarchs for a long time through many conflicts and crises. But how are they similar? How are they different? That’s a synthesis. It’s not easy to do.

It’s about stretching students’ minds and going beyond the superficial, and thinking in a deep way.

Isn’t this something that schools are already doing?

I admit both MI and synthesis are buzzwords. It would be easy to say, I used to teach “analysis” and now I teach “synthesis”. Or I used to believe there was one way to be smart, and now I believe there are other ways to be smart.

But teachers need to go deeper. This can’t be superficial. You need to have standards, in both cases. You can’t just say, “Oh, I’m doing synthesising”, or “I’m individualising and pluralising as the MI theory suggests”, and not think deeply about putting it into practice, reflecting on how you are doing, getting feedback on how you might do it differently and more effectively.

We need to be students of our practice, who learn from our mistakes and become more sensitive to the strengths of our students.

Howard Gardner was speaking to Kate Parker. His memoir, A Synthesizing Mind was published by MIT Press in 2020

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article