- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- ‘I’m leading a feminist revolution in my school’

‘I’m leading a feminist revolution in my school’

Is there really any need to focus on feminism in schools today? In a word, yes.

The teaching profession is hugely female dominated, yet leadership roles are disproportionately taken by men. Unhelpful stereotypes abound, from the playground to the staffroom. And “feminism” itself can still be seen as a dirty word.

Helen Mars, a secondary English teacher, is taking a practical approach to tackling the issue in her school. We asked her to explain how she is helping feminism to find a place in every classroom, for the sake of all students.

Tes: Feminism still often gets a bad rap these days, even among young people. Why do you think this is?

Helen Mars: There’s this idea that women need to stop campaigning because they have achieved equality. Feminism is often seen as outdated - complete with stereotypical ideas of feminists as “man haters”. However, we still do not live in an equal society and there is a long way to go before we do.

Why is it so important to address misconceptions about feminism right now?

We are educating young people in a time when they are bombarded with images and ideas about conformity and social expectations. In an increasingly online world, and against a background of toxic debate and “cancel culture”, schools and teachers are an important voice of rationality, information literacy and civil discussion.

What are some of the key points that you want your students to understand about feminism?

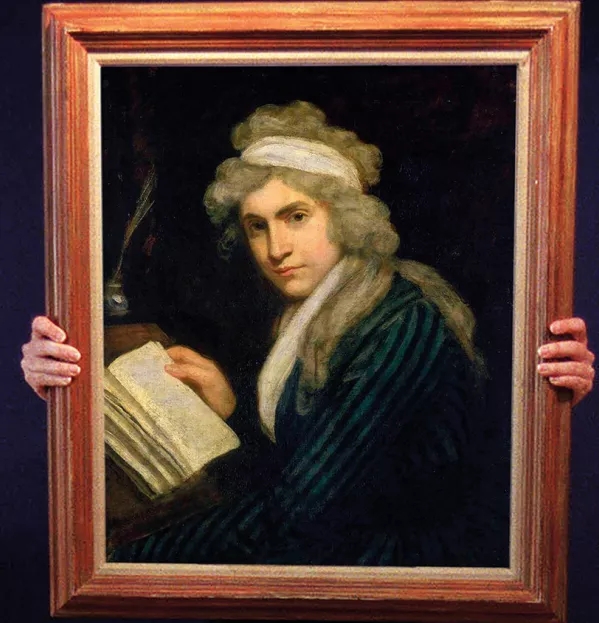

The history of why women’s voices are underrepresented is an important one. I teach English and Classics and, every year, students ask me why there are so few women writers, and if that is because they “aren’t as good”.

Explaining how women have been less educated in the past, but also how their texts tend to be dismissed or not saved for posterity - Sappho being the great example - is a natural way into discussions about canonical literature and the value judgements we make about texts and genres.

Talking about feminism doesn’t have to be explicitly political, either: just making time in a lesson or tutor time to unpick comments or to pose questions about how a person might be viewed differently if they were the opposite sex, for example, can make students consider a different viewpoint and their own implicit bias.

We would do this naturally if we heard a generalisation about any other group, such as a race or religion, and we need to be comfortable exploring ideas about sexism and feminism in the same manner, listening to students’ views and challenging problematic stereotypes.

Where does this fit into the school curriculum?

I teach the easiest course for assimilating feminist discussion: A-level English, where critical viewpoints like Marxism and feminism are necessary for effective study. I also teach a course for English literature on love through the ages, so ideas of social norms and gendered expectations are essential for understanding the texts in their historical context.

It’s not just a literary issue, though, and I have also taught PSHE and citizenship, where a scheme of learning about choices, relationships and sexual behaviours allowed a really useful discussion about how the students viewed stereotypes and double standards in terms of public perception and sexual behaviours. It was useful for boys and girls to have a space where they could talk about the pressures they felt and the strategies they could use to approach difficult issues in their teenage lives.

A colleague recently explained how she was delivering a drama lesson when a male student put on a stereotypical “girly” voice and mannerisms. So, she spent a couple of minutes talking to the class about stereotyping and how it can be harmful.

Feminism isn’t limited to the arts, either: ensuring that stereotypes are challenged, and that women’s achievements and contributions are acknowledged and celebrated in Stem subjects [science, technology, engineering and maths], is helping to broaden the aspirations of female students in areas where they have been historically underrepresented.

Teachers are required to remain politically neutral. Do you think it’s possible to teach about feminism and stay that way?

Absolutely. It’s of the utmost importance that we listen carefully to a variety of views - in the classroom and outside of it - and present them to students. That aids constructive debate, as well as modelling oracy and reasoning skills, British values and citizenship.

However, as with racism or any other kind of prejudice, it’s also important that we confront unacceptable views or language in the classroom, keeping our learning spaces safe from discrimination or factual inaccuracy. Being neutral doesn’t mean an absence of opinions, but giving a range of opinions, and ensuring that facts and opinion are clearly demarcated.

So, how can a school go about implementing these ideas?

First and foremost, a school needs to get its own house in order: ensuring that it has a representative governing body and senior management team, inclusive uniform, strong role models for both sexes, and scrupulously fair employment, pay and promotion policies.

Female voices at every part of decision-making processes mean fewer inadvertently unfair or discriminatory decisions. Schools need a robust behaviour policy that acknowledges misogyny, and schemes of learning incorporating key values and ideas in all subjects, not just PSHE.

As with “wellbeing”, inclusivity and feminism can feel like tick-box exercises when approached in the wrong way: to embed change, it needs to be a conscious and visible decision that is revisited and reiterated every day.

Discussing Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women with male colleagues has been useful as a way into exploring how we can make female staff safe, comfortable and empowered. Her explanations of the challenges faced by menopausal women, or unconscious bias in pay or hiring situations and how they can be overcome, for example, are fantastic.

What are some of the challenges that schools might encounter?

It’s easy to say that we already have enough to incorporate into lessons, but the fact is that women are still disadvantaged in many areas of their lives, and we have a duty to ensure that this 51 per cent of the population feels equally valued and as safe as their male counterparts.

We can’t afford to be defensive or to avoid difficult conversations. We have a duty to educate ourselves and be confident in promoting factual, fair and positive discussions with our pupils.

What outcomes would you ideally like to see? And how would you know that the approach is working?

If I walked into a school with equal numbers of male and female leaders, members of the science and poetry clubs, and where syllabuses in all subjects included great women, I’d be pleased. If I spoke to their staff and there was training to help girls be assertive in class, and there were policies to help staff deal with female issues like menstruation, breastfeeding and IVF, I’d want to apply for a job there.

And if I asked students what jobs they were unable to do because of their sex, and they told me they could do anything, if they rejected gender stereotypes and pursued their aspirations without fear, then I would want to send my children there.

Helen Mars is an English teacher in Yorkshire

This article originally appeared in the 5 February 2021 issue under the headline “How I... bring feminism into my school”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article