- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Secondary

- How a baseline reading test could transform whole-school literacy

How a baseline reading test could transform whole-school literacy

When Year 7 students arrive at South Shore Academy in Blackpool, they sit an important test, the outcome of which will shape their timetable for the next three years.

The test is the New Group Reading Test, provided by GL assessment. It measures reading skills against the national average and provides each student with a standard aged score (SAS).

This score will be used to determine which of several reading interventions pupils will receive throughout the school week: these are tailored to individual needs, with some students assigned up to four different interventions, each ranging from 20 minutes a day, to two hours a week.

If you’re thinking that running all of this sounds like a huge undertaking, you’d be right. But for Bernie Kaye, the school’s assistant headteacher, it’s well worth the effort.

“We’ve never been interested in quick wins and the whole focus on literacy is about playing the long game,” she explains.

- Ask the expert: is your classroom too noisy?

- How to put our broken support system back together

- What research says about motivating pupils - and ourselves

The school’s ultimate goal is to ensure that no child will be held back from accessing the full secondary curriculum as a result of low attainment in reading. But their focus hasn’t always been so clear.

“Five years ago, we didn’t do anything explicitly outside of English lessons for reading,” says Kaye. “We didn’t assess students, we didn’t run any interventions and we certainly didn’t know where reading was as a school.”

The Blackpool Key Stage 3 Literacy project

What changed? Well, in 2016, Blackpool was named an opportunity area. Government funding was awarded for education initiatives across the city, one of which was the Blackpool Key Stage 3 Literacy project, which focused on improving the literacy capability of all 11- to 14-year-olds across the town.

Six mainstream secondary schools were involved, including South Shore. Leaders were trained to deliver different evidence-based interventions for reading, and were supported to implement them into their schools. So how exactly does the intervention work at South Shore Academy?

As part of the wider project, leaders were taught about a range of interventions, but the school decided to implement four.

The first is Lexonik, a phonics-based programme that develops phonological awareness through metacognition, repetition, decoding and automaticity.

Next is Lexia PowerUp, which develops academic vocabulary through a personalised technology-led approach and accelerates basic reading abilities.

The third is Reciprocal Read QFT, which focuses on reading comprehension, and utilises teaching strategies like questioning, clarifying, summarising and predicting.

And finally, Precision Teaching, which is based on short one-minute tasks to build reading skills until they are fluent and automatic.

The school also uses paired and guided reading, as well as the British Picture Vocabulary Scale for English as an additional language (EAL) students.

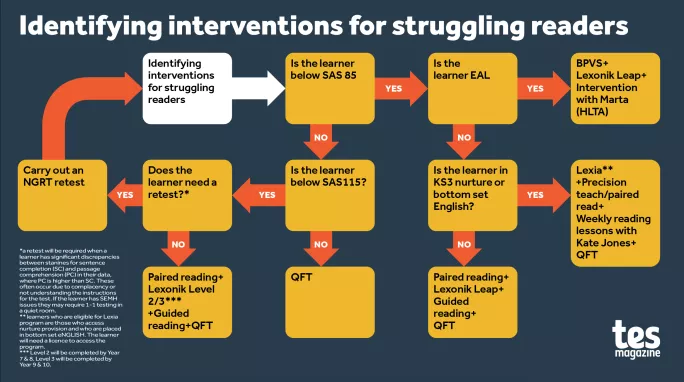

Kaye works with Kate Jones, the school’s reading intervention lead, to go through the SASs, one by one, and assign interventions using a flowchart (see below).

This flowchart was designed with the help of Dr Jessie Ricketts, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway, University of London, who is supporting all of the schools in the Blackpool Key Stage 3 Literacy project. She offered advice on which interventions are best matched to different needs.

While the average SAS is 100, at South Shore, the benchmark for needing no intervention is 115. A number of different factors help to determine which combination of interventions will best suit each student.

For example, if a child has a score of 71, doesn’t have EAL, but is in either the bottom set or the “nurture” set, they will have a combination of Lexia PowerUp, precision teaching, paired reading, a weekly reading lesson with their higher level teaching assistant (HTLA), and Reciprocal Read QFT.

Finding the time and resources to focus on literacy

It’s a substantial programme. So, how do South Shore find the time and resources to make it work? Some funding comes through the Blackpool project, as previously mentioned - and, as a result, the school has five HTLAs who all work full time, and do most of the intervention. Years 7 to 10 all have an assigned HLTA, with the other taking responsibility for the “nurture” classes.

But, to find the time within the school day, students have to be withdrawn from other classes. This isn’t ideal, Kaye admits, but it’s a sacrifice that has to be made to raise reading attainment. Some EAL students, for example, arrive at South Shore unable to read and write well, even in their own language, and that makes it incredibly difficult for them to access their usual lessons without intervention.

“We are really sensitive about subjects that we withdraw students from,” Kaye says. “But, ultimately, what it comes down to is that students need this provision. If they can’t read, they won’t be able to access the curriculum. We consider individual circumstances, and mix it up across the year.”

Crucially, the school takes precautions to minimise the subject content that students miss when removed from lessons: if the intervention is paired reading, for example, and a student is taken out of geography, the text used for the reading activity will be provided by the geography teacher.

On top of the personalised programme of interventions, all students take part in 40 minutes of guided reading at the start of every day. Three times a week this replaces tutor time, while the other two sessions have replaced a PSHE lesson and an assembly in the timetable. As a result, one novel, which is often linked to wider learning, is read by students every half term.

The big question is: is all of this effort worth it? Do the interventions work?

The evidence suggests that they do. At the end of each year, the students sit the New Group Reading Test again, and progress is statistically measured. When looking at the current Year 10s, the first group to go through this programme, the improvement is clear. When they were in Year 7, the average SAS was 86.2; today, it’s 94.6.

Progress across key stage 3 is also positive: SAS increased on average by 2.6 points per pupil between Autumn 2020 and Summer 2021, following on from an average 4 point increase per pupil since 2018.

How to replicate this approach

So, could other schools adopt a similar approach? Without the funding needed to hire additional support staff, and access to specialised training, it might be a challenge to make this work in the same way that it does at South Shore. Kaye also stresses that the chosen interventions work for their pupils, in their context, at the moment.

“We’re going to get to a stage where these interventions won’t work anymore, and we’ll need to think of something more stretching or more appropriate,” she says. “But at the moment, we are serving our community with the interventions we’ve got. It won’t be for everybody, but it certainly worked for us.”

However, Jones does have some advice for those leaders looking to replicate her school’s success. The first step, she says, should be implementing the initial baseline tests.

“The data speaks volumes and that’s is the best starting point,” she says. “From there you can tailor the interventions for students at all levels.”

Here, she says that it’s worth researching what works best for the students with the lowest SASs, rather than falling back on extra phonics tuition.

“Phonics for secondary school students can seem ‘immature’ and if it hasn’t worked by the time they reach Year 7, a different approach is usually needed,” she says.

“The data shows where, specifically, a student struggles, be that with word recognition or passage comprehension. So if word recognition is the difficulty, it is worth exploring precision teaching and British Picture Vocabulary Scale (BPVS). If a student struggles with comprehension it is often worth using the York Assessment of Reading for Comprehension, as this drills down into the specific difficulties they are experiencing.”

The key to success, then, is first identifying the needs of your students through a baseline assessment, before tailoring inventions specifically to them. As with so many things in education: context is king.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article