- Home

- Please, stop this squalid game of blaming teachers

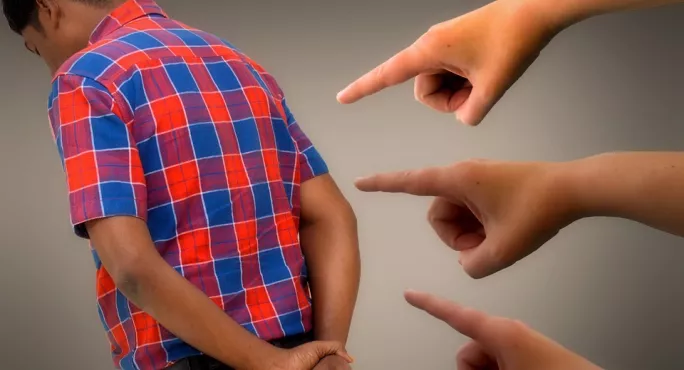

Please, stop this squalid game of blaming teachers

“Schools cannot go on like this indefinitely,” I wrote in my Tes column last week. The accompanying image was a frayed piece of rope on the verge of snapping.

I tried to set out the tremendous pressure on school leaders and their staff in managing Covid control protocols, amid spiralling infection rates in the community. I warned about the debilitating impact of this relentless pressure on mental health and wellbeing, and how this isn’t sustainable over the coming weeks and months.

And so it continues. This week, further evidence of the turbulence in our schools was provided by Department for Education statistics, which showed a big fall in the number of secondaries that are fully open, from 92 per cent on 17 September, to 84 per cent on 24 September.

You would hope that the government might respond to this deteriorating situation by demonstrating its support for schools and their staff, with some public recognition of the extraordinary efforts of public servants now on the frontline not only of educating our children but of keeping anxious communities safe and calm.

A cowardly kick in the teeth

Instead, from government, they got a cowardly kick in the teeth.

Because, in a manner of publication that was particularly gutless, the government used its powers under the Coronavirus Act 2020 to publish a continuity direction requiring schools to provide remote education to children at home.

To understand the draconian nature of this order, one only has to read the final paragraph, which tells us that the duty is enforceable by the secretary of state’s making an application to the High Court or county court for an injunction.

We can speculate about the government’s motivation. The requirement to provide remote education is already contained in the guidance issued by the Department for Education for full opening. There is a whole section setting out the expectations.

It is hard to see how the introduction of a continuity direction makes that requirement any clearer.

So, inevitably, the suspicion is that this is actually a piece of political posturing: a dog-whistle gesture intended to show a government getting tough with schools on behalf of parents. It is a nasty little message to send out to a profession that is already feeling beleaguered.

Sweeping judgements and generalisations

Of course, there is also a political trap for us. If we complain, the obvious retort is that those who aren’t doing anything wrong have nothing to fear. And the usual critics in certain sections of politics and the media will line up to remonstrate about the supposed failings of remote education during the lockdown.

Never mind the fact that schools had to turn round remote education for millions of children from scratch and in an incredibly short timeframe, and have learned a great deal in the intervening months.

Never mind that schools are now dealing with the task of managing complex safety protocols, while simultaneously delivering classroom teaching to most, and remote education to others, all at the same time, and with no additional resources.

The myriad commentators and pundits, looking on from their lofty perches on the moral high ground, are quick to issue sweeping judgements and generalisations about those actually doing the work in our schools and colleges. We’d like to think we could expect better more from our politicians. Those days seem long gone.

Making remote education work

So, let’s take head-on the issue at hand, which is the effectiveness of remote education, and examine what needs to happen to make it work as well as possible. Because there is a lot that frankly is not in the power of schools, however good the programmes they are running.

Many young people lack access to tablets or laptops, or have to share them, or do not have a stable internet connection, or do not have a quiet space in their homes in which to study. So, the experience of learning at home will differ widely depending on such circumstances, and these factors are most likely to affect disadvantaged children.

To its credit, the government is endeavouring to address those issues that can be addressed. In the wider announcement that accompanied the publication of the continuity order, it outlined plans to provide an additional 100,000 laptops for those children most in need, along with other support.

But is this enough? Buried in the accompanying raft of papers, we find an explanation of how it has assessed the level of need. The calculation is based on the number of children in Years 3 to 11, free school meals data, and an estimate of the number of devices a school or college already has.

Worryingly, however, this is accompanied by a caveat: “The exact number and type of devices available will be confirmed at the time of ordering based on stock availability and the extent of coronavirus (Covid-19) restrictions. If there are widespread school closures, allocations could be reduced.”

A squalid blame game

And if we delve deeper, we find a bizarre restriction. Devices, we are told, cannot be ordered for disadvantaged children, when a secondary school or college is operating a rota in line with local lockdown restrictions, or where there are fewer than 15 self-isolating children within a school.

One would have thought these are scenarios in which laptops would most definitely be needed. It is difficult to understand the rationale for this restriction. Unless, of course, there aren’t enough laptops to go round, and this is actually a way of limiting the numbers.

All of which leads us to the conclusion that we are some way off being able to ensure equal provision to remote education, and that the continuity order is irrelevant to the real issues.

Against rising levels of infection, an unspoken sense of panic and sometimes despair, this was the week when schools and colleges needed to hear that the government had their backs. It was when we needed to see a government replacing its tiresome world-beating rhetoric with action: getting testing sorted, playing its part in enabling remote learning to happen, refunding the spiralling costs of Covid measures.

Instead, we got a clumsily concealed legal threat, some incoherent messages about laptops, and another unneeded volley of political platitudes. It really isn’t good enough. Nor is the squalid accompanying blame game of making it all the teachers’ fault.

The mood is changing. Even more so than last week, we know that we cannot go on like this.

Geoff Barton is general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters