- Home

- Prison schools show exclusion is not the answer

Prison schools show exclusion is not the answer

Imagine that you are observing a lesson. It looks like any other classroom. The pupils look like any other pupils. And the teaching, you recognise that, too.

You sit at the back of the room while the teacher questions the group of teenagers and they take turns calling out responses.

It’s a food technology class. They’re making soup. Eventually, the pupils all turn to their paper to write down their notes.

It’s calm. It’s productive. Good kids. Good teaching. This is a good school.

Then you look at the external windows. Bars cover every single one. Air has to force its way in through the two-inch gaps of daylight.

You look right, at the classroom windows that face onto the corridor of the school. They are covered with a reflective film, you can’t see anything that is going on beyond them.

You become more aware of your surroundings now. You notice, through the small window in the door to outside, uniformed officers patrolling the corridors. You look again at the students cutting vegetables and you now notice that the knives are plastic, blunt.

It’s not so normal after all. It is a prison school.

I worked in prison education for 14 years. I started as a learning support assistant and when I left I was a headteacher. I got into it because I wanted to make a small change and I stayed because of the powerful pull of children with so many needs.

People have ideas about prison education. They have preconceptions about the children in those prison classrooms. They think of it as different, unconnected and separate to what happens in mainstream schools, in special schools and even in pupil referral units.

But it’s not. We need to pay more attention to prison schools, because this is where your excluded kids, your neglected kids, your disadvantaged kids, your kids with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), your unlucky kids and those kids who surprise you can end up.

People say the pupils we have are unteachable. That’s not true. The prison education system wants to show you it’s not true. And we want to reach out to try and stop these kids getting here in the first place.

Horrific crimes

Let’s not hide from it: some of the children I taught were in prison for horrific crimes.

Tyrone was 15. He was in prison for attempted murder after he had stabbed a rival gang member multiple times. The victim ended up in a coma.

Jason was 16. He was serving a 17-year sentence for a murder that had taken place after a burglary had “gone wrong”. He was verbally aggressive to staff and other students. He was a frightening and intimidating person to be around.

How do you begin to teach such children?

You have to get to know them. And when you get to know them you can begin to understand them, which is not the same as excusing them.

Tyrone later disclosed to staff that he had only joined a gang because he was so frightened of what would happen to him if he did not have “protection” in his area. Since being in custody, he had received no contact from any of his gang members, they had not written or sent him any money. He had realised that he had nobody.

After about a year of working with Jason, he disclosed that he still had night terrors almost every night where he relived the point that the victim was stabbed. He experienced regular flashbacks of the crime itself, yet was not able to access any post-traumatic stress therapy and instead was trying to “cope” with the images that would constantly present themselves to him.

We learned that the only reason he was even at the burglary was because family members had forced him to go as “lookout”. His main carer was in prison and the remaining family members were trying to care for the four children with no income.

When you sit down with these children, you find almost all of them have stories like Tyrone and Jason.

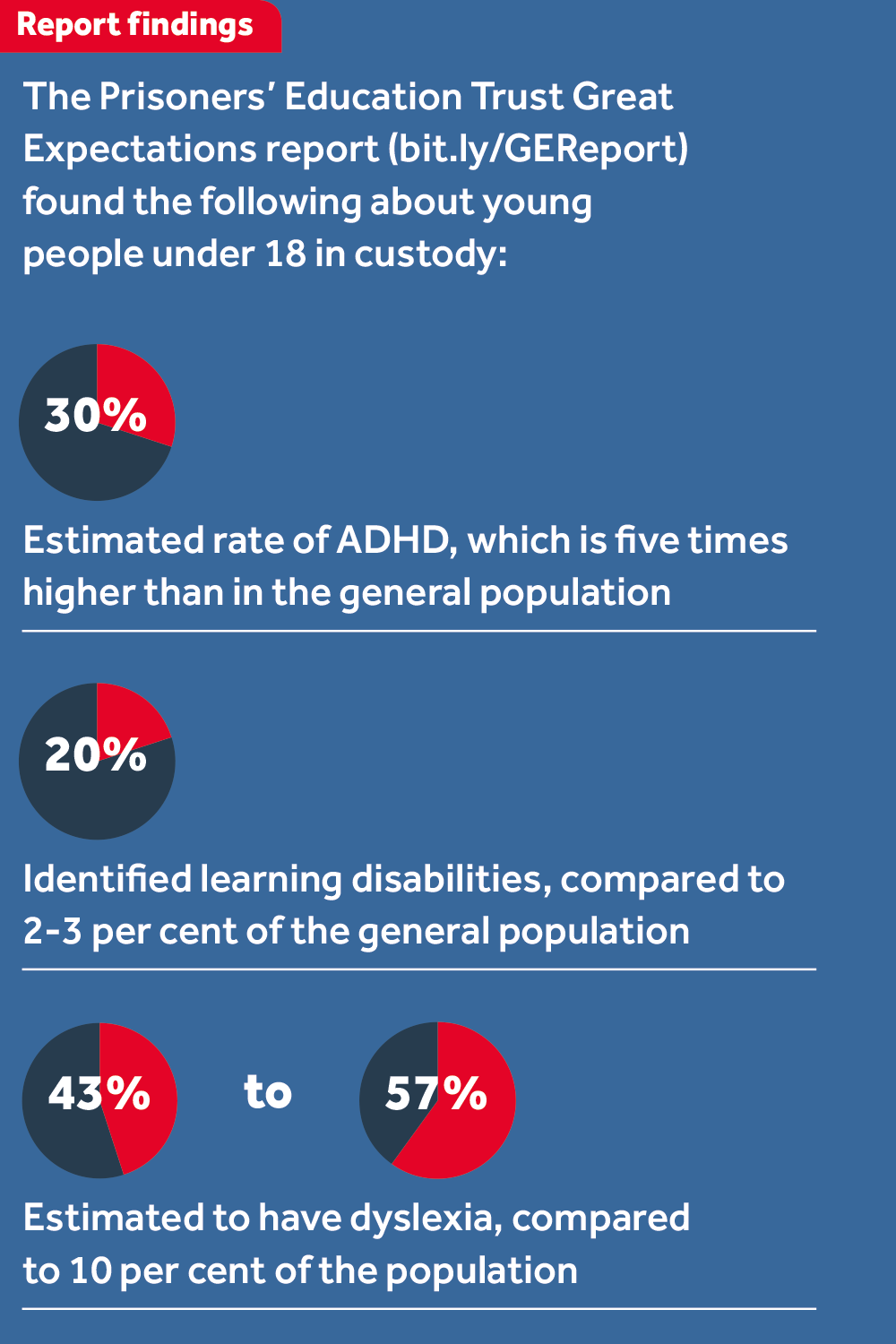

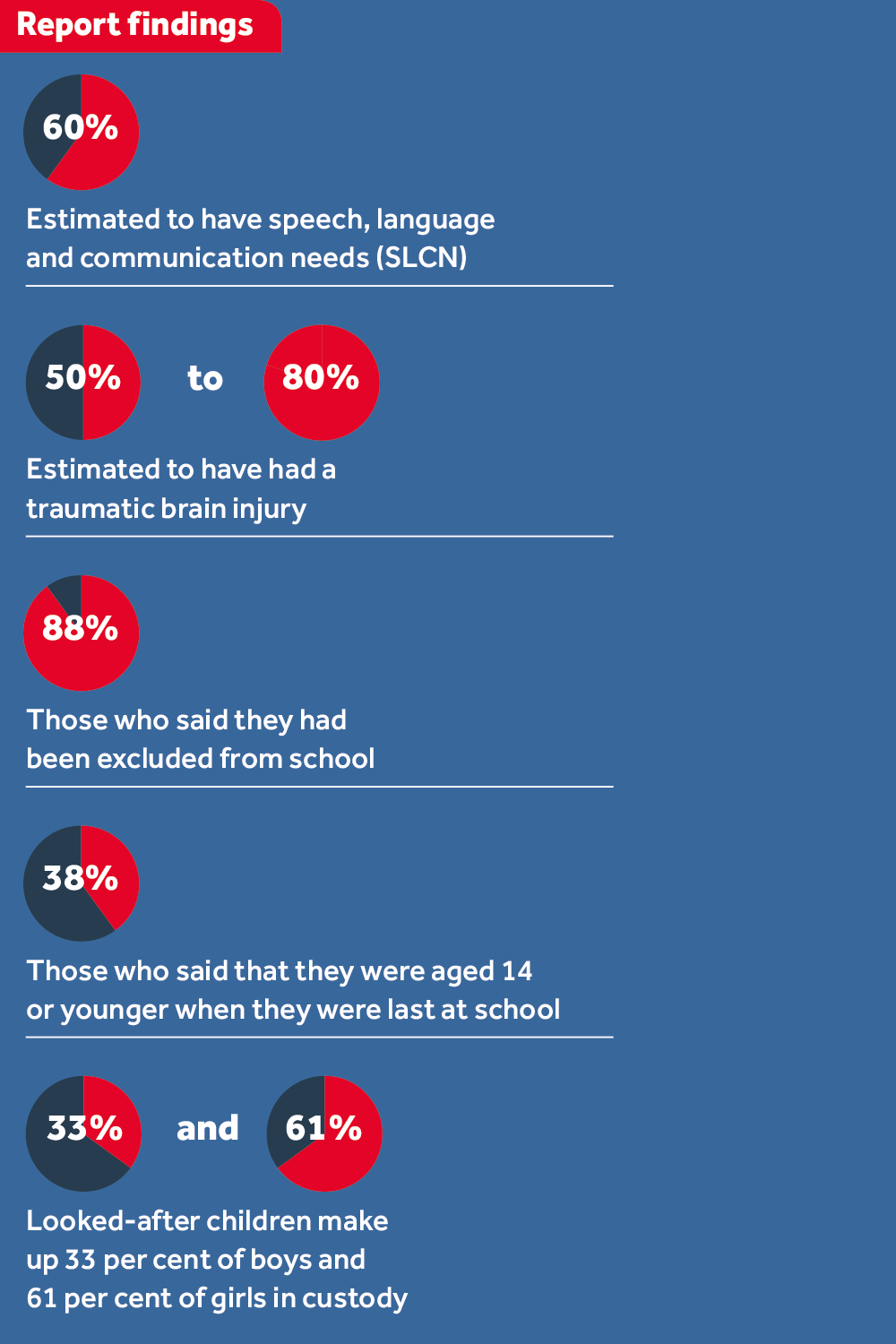

You also become aware that the potential to help themselves, through study and academic achievement, is not only hampered by their home environment, but also thwarted by complex and often undiagnosed SEND.

George had come to us with an education health and care plan (EHCP) defining his needs as co-morbid across ADHD, dyslexia and social, emotional and mental health (SEMH). He was unable to cope with the prison environment, specifically the confined space of a cell, meaning that when he came to lessons it was difficult to get him to sit in a chair or remain in one place.

George was unique because we never usually got that much information about a child before they arrived. We would often have children with clear SEND needs but no diagnosis - no information at all - and no strategies that could be used.

For example, Tyler came to us with severe mental health concerns. He had auditory and visual hallucinations that appeared in times of stress. He had been linked to acts of extremism and had fascinations with religious texts. Tyler did not have a formal medical diagnosis.

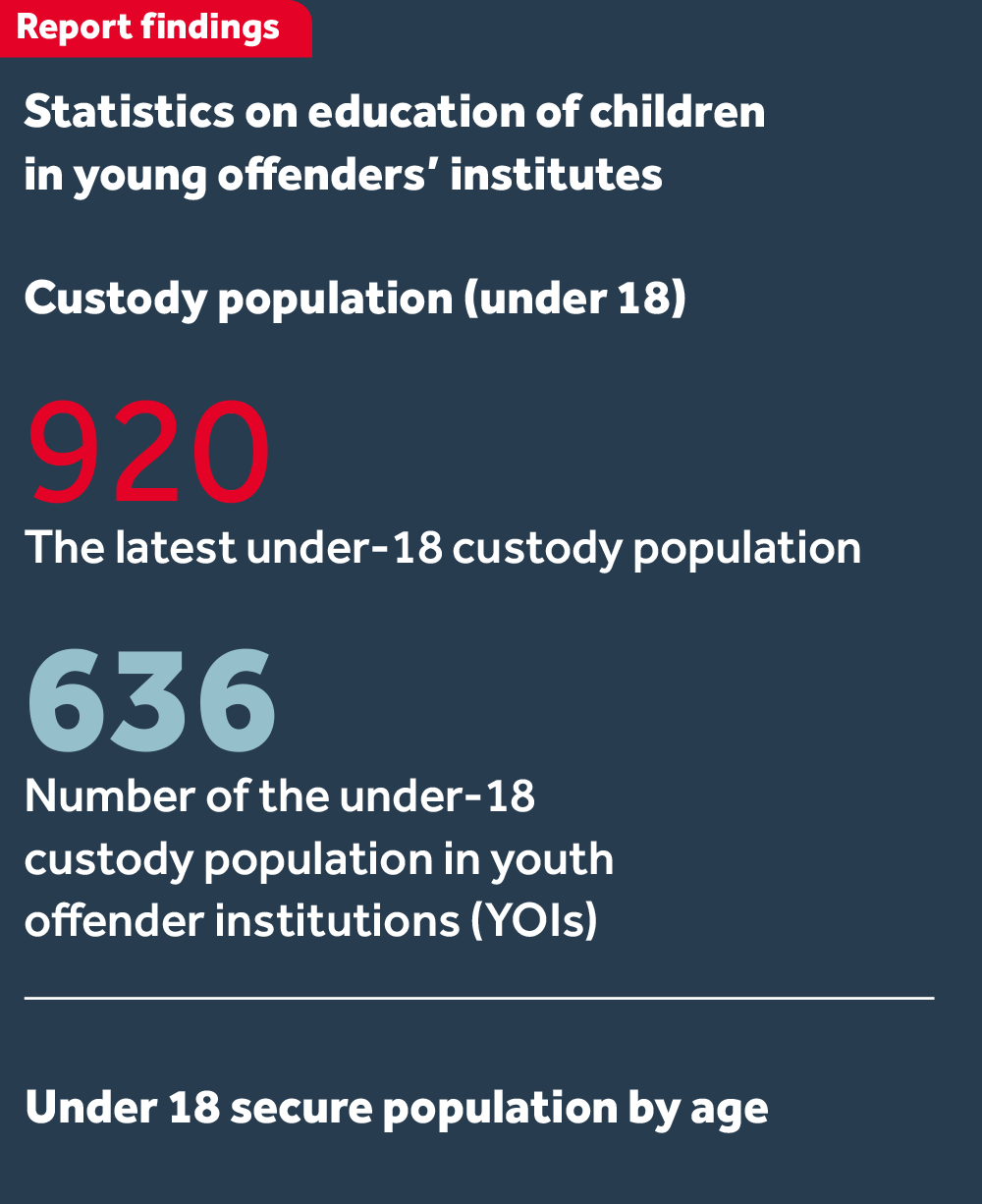

While headteacher, around 60 per cent of pupils in my school at any one time had SEND. As a former SEND coordinator, I suspected another 20-30 per cent of those students had SEND but had no diagnosis. In addition, an incredibly high percentage of the students had mental health issues.

As a teacher in a prison school, you might have Tyler, George, Jason and Tyrone in the same class - and with them would be up to eight other children, all just as complex.

How do you teach a class like that?

Essential assessments

The truth is, you know children like this. You probably teach them. The ones in my classrooms were just one action away from those in yours. But once they get in prison, and once you have a class where every child is that one child in a mainstream class, then things get really tough.

Initial assessments are essential. But attempting to motivate a 16-year-old boy to undertake an English and maths assessment when he has been charged with murder, has not managed to speak to his mother and does not even know when he will be able to, is a challenge. These students are angry, frightened, broken and fragile.

Compassionate and patient teaching staff get these children assessed and create an individual learning plan, along with all other aspects of planning that Ofsted would require.

What do we find with these students?

As mentioned, SEND issues are almost ubiquitous. That said, this does not necessarily translate to ubiquitous poor literacy. It is widely reported that many young offenders have below-average literacy skills. In my experience, this was not always the case. Dependent on the individual background of the student, we would get some children that were complete non-readers and others that were operating at A-level standard.

And personally? They present with all the typical traits of children with challenging behaviour: they do not trust adults, they do not believe in themselves and their aspirations disappeared along with their freedom.

Whatever is found, the teachers make a plan. The aim is to always enable the students to see a life beyond the prison walls and to prepare to become young adults.

That makes it sound simple. It isn’t.

I remember my first day as a learning support assistant. I walked through the grounds having all sorts of obscenities shouted out at me from the cell windows.

“Fucking slag. Look at her she looks like she likes it up the arse,” and “Suck my dick you fucking whore”. Trying to intimidate new staff members was a game favoured by many of the young people - they wanted to see how you would react.

What I did not know that day was how challenging it would be to make the smallest change in the lives of these students. What I also didn’t know was that if you managed it, the small changes you make in a school like that can have the most immense effect on the life of that student.

One boy in particular taught me that lesson. He came to us directly from a secure children’s home. He had been excluded from primary school and had transitioned straight to a secondary pupil referral unit (PRU). He had not set foot in a traditional classroom since the age of 7. He had been diagnosed with ADHD, SEMH, ODD and was co-morbid across a number of other areas of SEND. He was abusive, violent and unpredictable.

The first time I taught him, it was an unmitigated disaster. He spoke over me every time I attempted to teach. He threw things around the classroom, he wouldn’t sit in a chair and he circled the perimeter of the desks attempting to intimidate all the other students. He would do anything to create a disturbance.

I came out of the classroom hoping that he would be released on bail so I would not have to face him again.

Engaging their interest

But I went home that night and tried to remember everything I had heard him talking about, to see if there was a “hook” I could find to catch him with for the next lesson. He had spoken about a particular music artist. When I next taught him a few days later, I was ready with all my resources.

All the other students seemed excited by the theme of the lesson. He arrived and he mocked me in front of everyone for trying to make him “care” about my lessons. If I could have cried on the spot, I would have.

“I want you to care, because I care,” I told him.

He looked at me intently. “You don’t care. Show me you care, then.”

“I can only do that if you let me teach you. If we can’t respect each other, then we aren’t going to get anywhere.”

I decided I would just try and continue with the lesson. He wasn’t perfectly behaved, but he engaged - and, with this, the other learners did, too.

At the end of that day, I went over to his cell to speak with him through the window. I asked him what it was he needed from me to show him that I wanted him to learn.

“I just like showing people I can intimidate them, but I saw how upset you looked when I was going to ruin your lesson so I changed my mind,” he replied.

He didn’t realise it, but he was saving me that day. He taught me how to feel what they feel. They felt that they were being mocked and they felt powerless: they couldn’t decide when to eat, when to sleep or when to shower. But they could decide how they treated people. So they often decided to treat them badly.

As teachers, our job was to make them want to treat us and themselves better and that was a challenge that continued from the day I started the job until the day I left.

Relevant curriculum

So how do you manage to do that in a prison school?

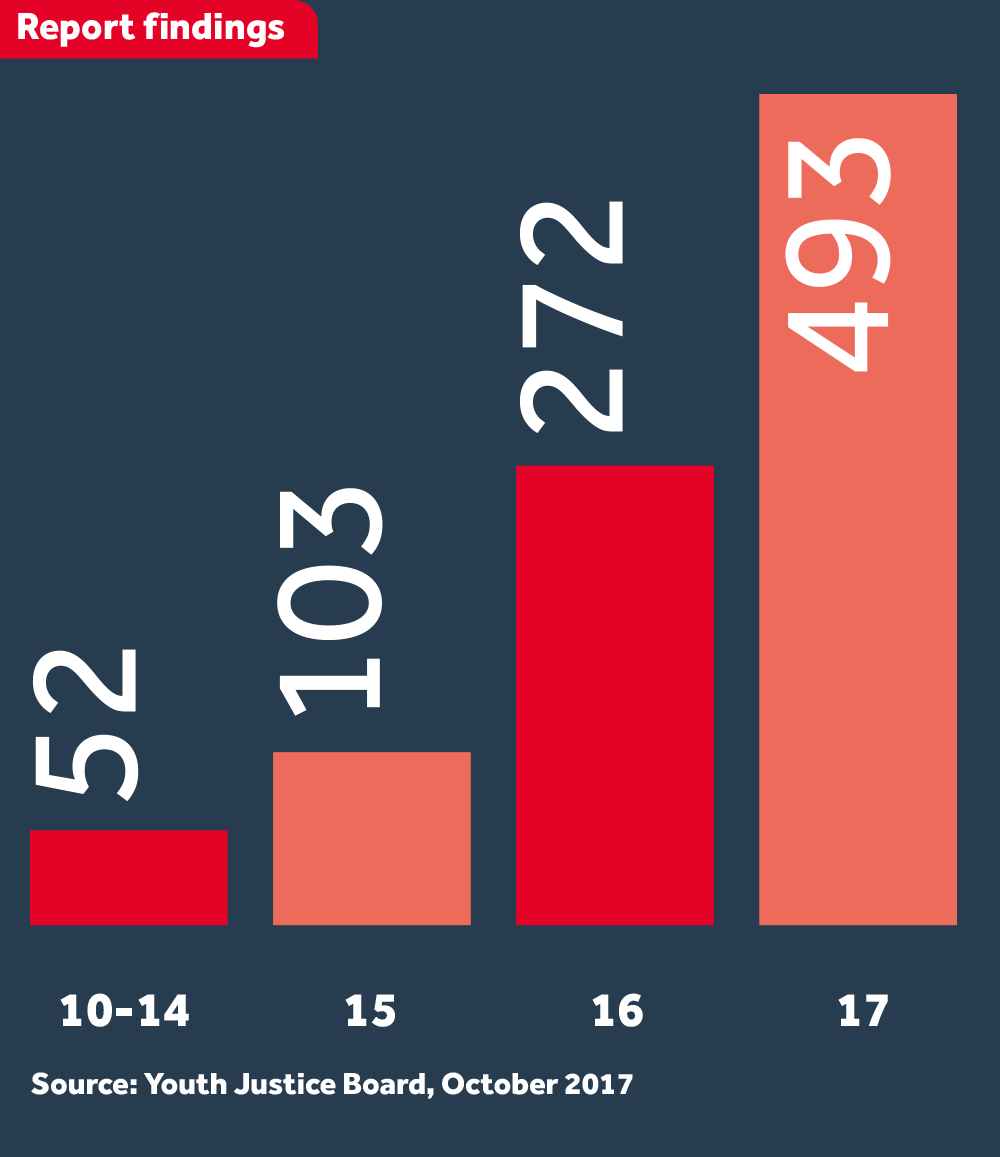

No excuses does not work here. You can’t scare them, you can’t exclude them. Usually, these are the children thrown out of mainstream schools: up to 90 per cent of the children in prison have been excluded from school. It didn’t work. It didn’t shock them onto a different path. It accelerated the one they were already on. You have to find another way through.

Expectations were important, as was prevention: getting children to behave started and ended with what they were being taught and how.

Attempts to make the curriculum relevant were consistently at the forefront of planning meetings, with a focus on how to help set them up on their release.

Vocational subjects were always the most popular, specifically music technology and catering and hospitality - but, with limited space and resources, these courses were always oversubscribed.

And pedagogy? The majority of these learners did not like or enjoy school and the last time they did was primary phase. With this in mind, a lot of the teaching styles in our school were based on primary pedagogy, with praise, rewards and encouragement to continue to motivate them to engage.

For example, we introduced an incentive passport and students would collect stamps over a six-week period, very much the same as a skills passport in mainstream. Students could submit their passport if they had collected 60 stamps and achieved five of their academic targets. We would cook a proper home-cooked meal as a reward.

Out of all the schemes we attempted, this was the most successful. It was about showing them how proud we were of them - and it was amazing to see how something as simple as this could incentivise these boys to work hard. They were prouder of those passports than anything else - they would protect them over anything else. When they got to this point, the learning and motivation accelerated and these students became a captivating group of children to work with.

Does all this work? It depends on your definition of success.

In Tyler’s case, support from the clinical psychology team, the chaplaincy team and the teachers meant that successful strategies were found.

George was given a “fiddle” object for classes and he had one-to-one support for his literacy. He refused to take his ADHD medication, and interestingly over the course of a few months he had developed coping mechanisms himself, supported by the school. He had a time-out card, he was given lots of puzzles and he had things provided in his cell to keep him occupied when he was confined. He began to thrive.

Getting Jason engaged when he had a 17-year sentence was tough - but teaching staff managed to motivate him. He achieved his level 2 functional English and maths and numerous vocational qualifications before moving onto his “lifer” prison. His use of inappropriate language subsided, he learned manners and he produced some fantastic music. These outcomes were all achieved by the sheer determination of staff to recognise his struggles and support him - despite not being PTSD specialists, the pastoral elements of teaching were crucial to overcoming the daily struggles that Jason was having.

Other students have gone on to work for charities, some are professional mechanics and one is even a professional heavyweight boxer. I could not be prouder of these children now that they have grown into independent adults.

But ultimately, this is a prison. Our intervention was often too late.

I have taught children who have been released, only to be murdered when they go back into the community. I have seen so many reoffend. I have seen broken children at their lowest point. I have worked with children that communicate in the most difficult ways and those that only know violence. I have seen a child soil himself in the middle of the corridor through pure fright when he saw a rival gang member. I have seen children curl up and cry while reliving the horrific crime that they committed and that they continue to relive night after night in their cell.

I have had the sense of dread wash over me a number of times when the alarm bells go off and you see a mass brawl in the school corridor and you hope that an improvised weapon has not been involved. I have cleaned up the blood on the walls and the floors.

You have to ask yourself: how did we, as a society, let children get to this point?

I left the prison school because I was frustrated at being at the end of the chain when there was simply too much to do. I moved to take charge of a PRU, to try and be that intervention point further up the chain. I felt like I was abandoning them. It was one of the hardest decisions I have ever made.

But most of the young people can clearly articulate the point at which their life started to go wrong. If teachers in mainstream schools and PRUs can intervene where possible when these points are occurring, this may be the point at which the child is saved from a world of criminal behaviour. This is the point they need us most.

It is not just about schools, but it is often schools that will be able to spot the issues at the earliest point. So much great work is done already by brave and excellent teachers, but so many more schools need to understand that troubled kids are not a nuisance, they are not irritants to be silenced, they are not disruptions that need to be disposed of.

Changing mindsets

Exclusion is often the catalyst for negative change, not a wake-up call for a transition to better behaviour. We have shown that given the right conditions - and the right interventions - these children can be taught and be taught alongside others.

Should any child be denied a mainstream inclusive education because of where and to whom they were born? I don’t buy that at all. If the child is a threat to others, then the law needs to be followed, but the signs of trouble will have been there for some time: we need to change our mindset with children before they get to that point. We need to stop throwing them away.

To do that, schools need support. Other services have to be ready to step in with effective action. Too often, teachers spot the signs but a child is left on a path to prison because the government support is simply not there. And society, as a whole, needs to play its part too.

I have seen what happens to children left in desperate situations. I have seen what a failure to intervene early enough can do. I want to shout about it - and prison education needs to talk about this more - because I believe we can make a change.

The solution is simple: the children need help and support. Most of all, they need us to care - and to show that we do.

The writer wishes to remain anonymous. Details of the children in this article have been changed in order to protect their identities.

This was first published in Tes magazine on 16 Feburary, 2018.

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters