Investigation: How vulnerable pupils are still hit with digital disadvantage

Of the many ways in which a pupil can be disadvantaged at school, digital disadvantage is one that was usually a long way down the list pre-pandemic. A pupil’s access to devices, fast internet or other digital tools was often masked when it affected only homework, but the onset of large-scale remote learning when Covid hit suddenly put technology front and centre.

Data from SchoolDash, shared exclusively with Tes, lays bare the extent of the problem. It found significant differences in access to technology, schools’ tech spend and connectivity across different regions of England - and, although it is difficult to tie this growing tech inequality directly to academic results, experts believe the digital divide could be having a significant impact on learning and pupil outcomes.

Moreover, the situation could be about to get worse given that, post-pandemic, more online learning is taking place even though face-to-face learning has resumed.

So, just how bad is the problem at the moment and what can be done to address it before it exacerbates?

Poverty and the pandemic

It’s difficult to say with any certainty how big a technology problem there was prior to the pandemic as there aren’t any hard and fast numbers on how many school-age children have access to an internet-enabled device and to the internet. However, Timo Hannay, founder of SchoolDash, says there are certain assumptions it is safe to make.

“I think it’s fairly self-evident that poorer communities and poorer households are going to be less replete with devices, whether it’s smartphones or laptops or whatever, than the more affluent households and communities,” he says.

“In a way, it’s always been a bit of a chronic problem, but I think what happened during the pandemic was that it suddenly became an acute problem. It’s an increasing problem in the sense that education and learning has come to depend more and more on internet connectivity and devices.”

Hannay says that online learning had grown slowly in the years building up to the pandemic, with more children doing homework online or using devices connected to the internet to research essays.

Then when the pandemic occurred and millions of children were stuck at home, the only learning available to them was online. But if those children didn’t have access to their own device - many parents were working from home at the time using devices and the internet - or didn’t have access to the internet, then they didn’t have access to learning.

The legacy of the pandemic means these difficulties have continued for some: online learning is now more commonplace than it was at the tail end of 2019 to early 2020. “When we look at the usage data, it’s obviously not as big a thing as it was during the pandemic, but it’s still a bigger thing than it was before the pandemic,” says Hannay. “There is definitely a switch to more homework, more revision, more educational activities and ancillary activities like consultations moving online.”

Huge variations in access

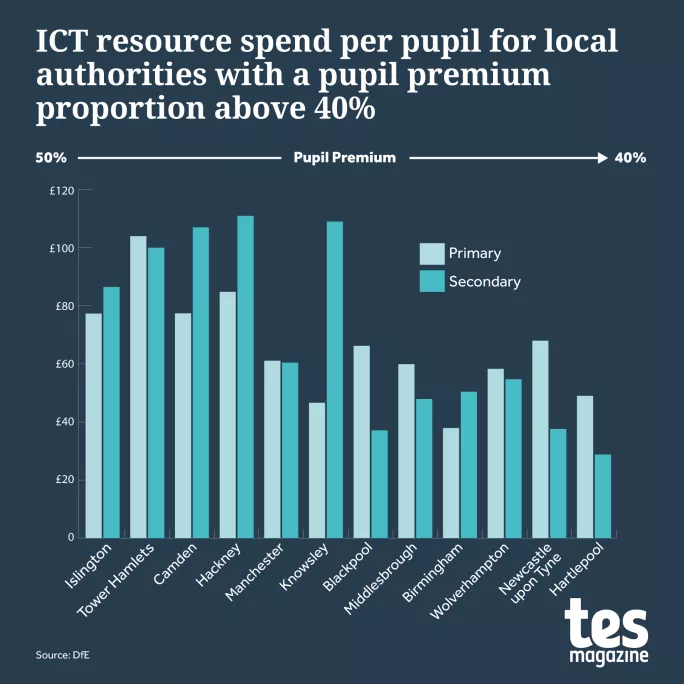

What’s striking about the SchoolDash data is the variation in spend on technology across England. When you take the 12 areas with the highest pupil premium (more than 40 per cent), primary ICT spend ranges between £37.90 and £104 per pupil, and secondary ICT spend ranges between £28.80 and £111 per student.

The variance is consistent across all levels of disadvantage. For example, in the least deprived areas (less than 20 per cent pupil premium), the ICT spend range for primary is £16.10 to £102 per pupil, and for secondary £4.50 to £104 per student.

James Browning, chief operating officer at AET Schools, says that while it is somewhat stark to see the variance laid out so clearly, he doesn’t think the findings are altogether unsurprising.

“What’s driving the spend in each area is, bluntly, how each school or trust prioritises the expenditure on technology alongside other budget decisions,” explains Browning. “Some schools invest in just the essentials - such as an MIS [management information system] and some form of connectivity - whereas others will place technology right at the heart of what they do and how they teach.

“As a result, they invest much more heavily in devices, platforms and specialist staff to support the rollout. If, for example, a school relies on using devices in every lesson as part of their teaching model, then that in turn drives the need for more routers and spend.”

Browning adds that the wide variation across schools in England has been created because there has been “no clear and consistent expectation” across the sector and “what it really comes down to is whether schools see technology as a strategic driver of what they do, or not”.

Closing the digital divide

At the height of the pandemic, some of the most disadvantaged children living in the poorest areas of the UK effectively received a temporary reprieve from this digital deprivation as schools, charities, trusts and local authorities had to put in place measures to close the gaping digital divide.

The Northern Education Trust sponsors some of the most deprived schools in the North of England and Rob Tarn, the trust’s chief executive, says that during the pandemic it became apparent that many children did not have an up-to-date device they could use for their sole purpose.

“Across the country, children in deprived areas really struggled to access online lessons during the pandemic, and something as simple as an internet connection was out of reach for many students,” says Tarn. “For many families, there may be one device shared between the whole family, or sometimes no device at all. The trust ensured that all students who needed a device were provided with one so that they could access their education online.”

Over the past two years, the trust has distributed around 2,200 devices at a cost of £67,000 to the trust, and these devices have not been recalled since the pandemic measures ended. The trust also secured funding for the device rollout from the DfE.

Tes recently featured a similarly huge tech rollout conducted by Oasis Community Learning.

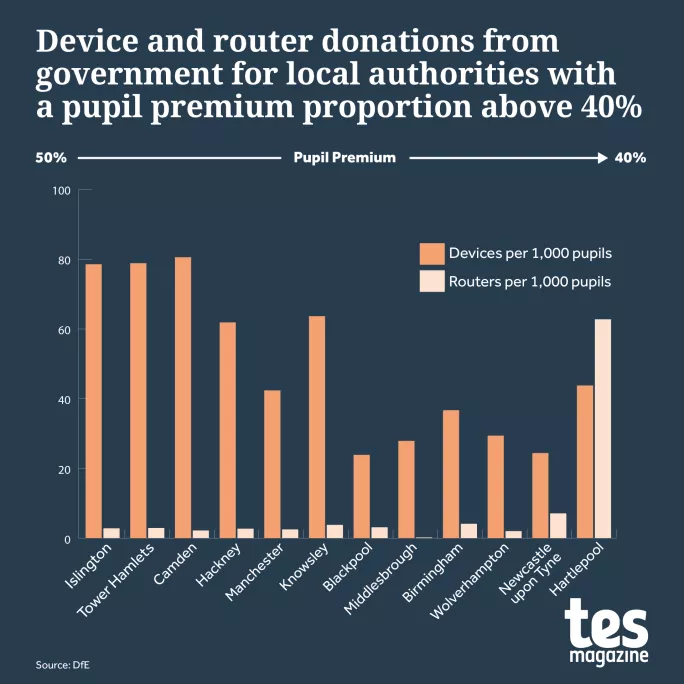

Additionally, during the pandemic, the government provided 1.95 million laptops and devices to children from poorer families. It also gave free mobile data to more than 33,000 disadvantaged children and delivered more than 100,000 4G wireless routers for pupils without an internet connection at home.

The DfE says that allocations were based on the number of children in receipt of free school meals, but the SchoolDash data shows that distribution of devices in the most disadvantaged areas was again highly variable.

In terms of devices donated per 1,000 pupils, this ranged from 23.9 devices in Blackpool - which had an ICT spend of £66.20 per pupil in primary and £37.10 in secondary - to 80.6 devices in Camden, which had a per-pupil ICT spend of £77.40 in primary and £107 in secondary. And in terms of the distribution of routers per 1,000 pupils, this ranged from 0.2 routers in Middlesbrough (which spent £59.90 and £47.90 on ICT in primary and secondary, respectively) to 62.8 routers in Hartlepool (£49 ITT spend per pupil in primary; £28.80 in secondary).

Hannay says the SchoolDash data only tracks distributions handled by local authorities and it is possible that devices were handled via other routes, so some of the most poverty-stricken areas did receive more devices.

However, he adds that there is also a possibility that even though the DfE criteria for distributing devices clearly stated that they should go to areas with high numbers of pupil premium children, there is a possibility that some poorer areas didn’t receive any devices, or received fewer devices than intended, and missed out.

A swift Covid response

On the flip side, he credits the Department for Education for acting so swiftly in distributing devices and routers and says that some of the work SchoolDash has undertaken appears to show that the rollout did make a difference.

One piece of research SchoolDash undertook, with Nesta, looked at usage logs from edtech companies across primary and secondary school pupils.

“During the course of the pandemic, we could see lower proportions of access history through mobile phones and higher proportions through computers,” says Hannay. “We could also see the shift whereby, to begin with, children in poorer areas were more likely to be accessing those services on a mobile phone, and as time went on, particularly during the course of 2020, that gap closed. And so, by spring 2021, you could see that, actually, there was no longer such a big gap between poor areas and more affluent areas.”

He adds that it’s hard to know with any certainty if this shift in the data was as a direct result of the DfE’s intervention, but he says the numbers do appear to be consistent with the idea that if you give away nearly 2 million devices to poorer areas you would expect computer access in those areas to improve - and, according to SchoolDash data, it did.

Hannay also says it’s hard to quantify how big an impact the potential digital divide in England is having on educational outcomes at the moment because the pandemic still looms large in the rear-view mirror and it’s too early to say with any degree of accuracy whether or not it widened the divide. However, he fears the worst.

“If we’re in a world where kids are using technology more and more for their learning, but there’s a disparity in their access to the technology, it seems almost inevitable that would add to the educational disparities that we already have, which are obviously worse now coming out of Covid than they were before,” he explains. “We don’t yet know the scale of the problem. We’re sort of anticipating that there will be a problem unless there’s something done to address this difference in access to technology, which was addressed during the pandemic, but has disappeared since.”

John Roberts, product and engineering director at Oak National Academy, points out that the issue is not necessarily just children not having access to digital devices and the internet, which puts them at a disadvantage: he thinks it also potentially limits the ability of teachers to teach.

“When technology relies so heavily on the internet, where connectivity is poor, teachers are less likely to plan lessons that involve technology so they miss out on making full use of the best resources available,” he says. “It also risks adding to their workload if they cannot quickly and reliably get access to good online resources. That is something we really need to be aware of.”

What next for schools and tech?

So, if we accept that a technological inequality exists among schoolchildren in England and at the same time we also accept that we don’t really know the true scale of the problem, what can be done to fix it?

Roberts says that, owing to the budgetary constraints schools currently face, many will struggle to invest in both devices and the digital infrastructure that supports them.

“Significant ongoing investment is going to be required to match the standards required by the DfE,” he adds. “This is particularly true in small primary schools where IT administration may fall to one individual, or there is remote-only support.”

AET’s Browning says that, from the work he has done with the DfE, it is “acutely aware” of the issue and the main way it is looking to address it is through its work on digital standards.

“I’ve been a member of the working group that is driving this work, and the standards are designed to be used as guidelines to support schools in using the right digital infrastructure and technology,” says Browning. “More standards are being added as the full plan is worked up, but there are already good guidelines for broadband, networking and cybersecurity.”

As for the DfE, a spokesperson for the department says it is “committed to ensuring that every child in England has access to the technology they need to learn and thrive. That’s why during the pandemic, we provided 1.95 million laptops and tablets to help children learning remotely, as well as support for 130,000 families to get online”.

The spokesperson added that the government is also investing up to a further £150 million to “upgrade schools that fall below our wi-fi connectivity standards in priority areas so that schools can make the most of the benefits that digital technology can have in the classroom”.

Whether this will be enough to solve the issue of technological deprivation in England remains to be seen. What we do know is there is a number of children who don’t have good access to devices and the internet in the country at the moment, and if technology is becoming an increasingly central part of education - which all the evidence suggests it is - then there will be a divide, and the question then is: how do we span that divide?

“We should be thinking about it because there are still all sorts of disparities [in the education system],” says Hannay, “and if we don’t address this one then this technological divide is going to be another inequality in the education system to add to all the others.”

Simon Creasey is a freelance journalist

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article