- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- What exactly is maths mastery, anyway?

What exactly is maths mastery, anyway?

Maths mastery, if you listen to certain people, is the success story of the past 10 years of English primary education. It has transformed results, levelled the educational playing field and will form a key part of post-Covid recovery.

The government is so confident in it that it has spent £100 million on its Teaching for Mastery (TfM) programme.

But there’s a problem: what some people believe to be maths mastery actually isn’t the version of maths mastery in the government narrative. Worse still, the government’s version has a lot less evidence behind it than you might think.

Most teachers involved in maths mastery believe its roots lie in parts of South East Asia and East Asia, such as Singapore and Shanghai. This is because the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics (NCETM), the government-funded organisation that developed the TfM programme, draws its influences from here.

But there are alternative approaches that also use a “mastery” badge. One is Complete Mathematics, operated by La Salle Education, which uses “goal-specific quizzes [to] ensure [that students reach] understanding at a ‘mastery threshold’ before moving on”.

Another is Mathematics Mastery, developed by Ark Curriculum Plus. Although also underpinned by East Asian and South East Asian methods, Ark’s programme looks different from both of those mentioned above.

“There are so many different views on mastery,” explains Mark Boylan, a professor at the Sheffield Institute of Education, Sheffield Hallam University, who led a 2019 research review into the TfM programme.

“Mastery means lots of different things to different people. When you ask me ‘what is mastery?’, I have to ask: which mastery are you talking about? Are you talking about a particular approach to teaching? Are you talking about the intended outcome for pupils?”

Maths mastery: different definitions

East Asian and South East Asian maths mastery, in the TfM guise, involves all pupils being taught through “whole-class interactive teaching”.

The principles underpinning this approach originate in 1980s Singapore, where, in a bid to address the country’s low performance in maths, experts came up with a new teaching method based on the work of US psychologist Jerome Bruner, British educationalist Richard Skemp and Hungarian mathematician Zoltan Dienes.

The result was an approach that involves all pupils working on the same lesson content at the same time, with no ability groupings. Teachers lead the whole class through one mathematical skill or concept at a time, ensuring that every pupil reaches “mastery” of that concept before anyone moves on to the next.

In contrast, Mark McCourt, the director of La Salle Education, explains that an earlier version of mastery, commonly used in schools today, actually stems from the work of US educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom in the 1960s.

“Bloom’s mastery is the idea that, given the right conditions, and the appropriate amount of time, the majority of pupils can be successful in every subject,” McCourt explains. “Rather than assuming that in every class there will be some pupils who learn well and some who don’t, mastery challenges this and says it’s because the learning conditions aren’t right.”

‘When you ask me “what is mastery?”, I have to ask: which mastery are you talking about?’

Bloom’s approach involved teachers chunking subject matter into units with specific learning objectives and outcomes. Learners were usually required to demonstrate mastery by scoring at least 80 per cent on unit tests.

If they did not reach this, they would be provided with extra support but had to continue the cycle of studying and testing until the threshold was met.

Unlike East Asian and South East Asian mastery, though, there is no expectation for whole-class, teacher-led instruction, and students may not all work on the same lesson content at the same time.

This distinction between the two definitions of mastery is critical when it comes to looking at the evidence for effectiveness - because Bloom’s definition has a much larger evidence base.

According to the Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit, when implemented well, the Bloom version of mastery learning has an average impact of an extra five months’ progress over the course of a year. And the toolkit makes a clear distinction between this and more recent East and South East Asian-inspired mastery approaches, which do not share all the characteristics of the initial approach.

“‘Mastery learning’ should be distinguished from a related approach sometimes known as ‘teaching for mastery’. This term is often used to describe the approach to maths teaching found in high-performing places in East Asia [and South East Asia], such as Shanghai and Singapore,” the toolkit states.

“Like ‘mastery learning’, ‘teaching for mastery’ aims to support all pupils to achieve deep understanding and competence in the relevant topic. However, ‘teaching for mastery’ is characterised by teacher-led, whole-class teaching; common lesson content for all pupils; and use of manipulatives and representations.”

The EEF adds that, “although some aspects of ‘teaching for mastery’ are informed by research, relatively few interventions of this nature have been evaluated for impact”.

So, has the government picked the wrong mastery to implement? Debbie Morgan, director of primary mathematics at the NCETM, says not.

She argues that while there is a need for more research, the results of England’s shift towards the government-backed version of mastery speak for themselves.

As well as “lots of feedback from schools on how TfM is making a difference in closing the gap”, we can look to the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss) test to see the effectiveness of mastery, she says.

In the 2019 test, 10-year-old pupils in England scored 10 points higher in maths than those included in the 2015 study, and England climbed up two positions in the rankings, from 10th to eighth. However, England’s 14-year-old students’ maths performance decreased slightly, which meant England slipped two ranking positions, from 11th to 13th.

“Very few countries made a statistically significant gain,” Morgan says. “This says there is something different going on that wasn’t going on before. The biggest change in England is teaching for mastery. It’s legitimate to say we are heading in the right direction.”

More on maths mastery:

How education research gets lost in translation

Revealed - who decides which maths mastery books are DfE-funded

Three adaptations for SEND students when using mastery

Anne Watson, a professor emeritus at the University of Oxford with decades of experience in maths education, disagrees that we can directly chalk those results up to maths mastery.

“When you look at international research about mastery versus something else or direct instruction versus something else, there are specific circumstances that mean the research isn’t applicable in the UK,” she says.

In a recent Tes article, writer John Morgan explored some of these circumstances. He found that “differences in educational culture around maths and the experiences Singaporean children have had before Year 1”, along with other cultural factors, make it difficult to transpose pedagogical approaches from Singapore to the UK - and when we try, it is not reasonable to assume those approaches will have the same effect.

To complicate things even further, the two versions of mastery explored in this article are by no means the only versions.

Indeed, there are multiple types of mastery that schools are using, so if you can attribute Timss results to how we are teaching maths, then it would be a mixture of these methods, not just the government-approved method, that could take credit. Take Ark.

When it built its Mathematics Mastery programme in 2010, it did look at Asian countries but it also looked at other sources of evidence, too.

Tim Oates was a member of Ark’s advisory group, and brought with him knowledge of high-performing jurisdictions across the world, thanks to his work on the national curriculum between 2010 and 2013.

Helen Drury, director of curriculum programmes at Ark, also points to her own experience as a member of the expert panel writing the primary and secondary maths national curriculum.

“I became particularly interested in learning more about the maths education in the higher-performing jurisdictions Tim identified - so Finland, Hong Kong, Massachusetts and Alberta as well as Singapore,” she says.

“What I was really interested in was how those jurisdictions (and others) had taken the research evidence about effective maths teaching and curriculum (much of it from UK research institutions) and supported schools and teachers to implement it in the classroom.”

And even though it was the first time the word “mastery” had been used in relation to East Asian and South East Asian mathematics, at least in England, Drury says it was probably not the right term to use considering its current connotations.

“In hindsight, we should have called it Ark maths,” she says. “But it was about pupils having mastery of the subject and developing deep understanding. It was about mastery for all; not an approach to teaching where people either sink or swim.”

Drury says she doesn’t consider Ark’s programme to be an East Asian maths system.

“It was never our intention to borrow from or mimic other jurisdictions, so no, I wouldn’t consider Ark’s Mathematics Mastery to be an East Asian maths system,” she says.

“However, our work did influence the Department for Education, NCETM and maths hubs’ work, so if we want to call that ‘an East Asian maths system’, then it’s fair to point out that we share a lot of features with that.”

‘There are sometimes quite big differences between what people’s understanding of the term is and what teaching for mastery looks like’

Another major influence in this space is White Rose Maths. Originally a maths hub, White Rose now has resources that are used in thousands of schools across the country. On its website, it says “helping students on their journey towards mastery is exactly what White Rose Maths exists to do”.

However, Caroline Hamilton, managing director of White Rose, says the organisation does not tether itself to “mastery”.

“We don’t use the phrase much at all in our work. It might pop up a bit, and we’re not against the word ‘mastery’, but it is one of those buzzwords,” she says.

Hamilton and her colleague Tony Staneff, head of external initiatives, do use the NCETM’s big five ideas - coherence, representation and structure, mathematical thinking, fluency and variation - to inform their work, though, and agree that all pupils should understand the material before they move on to the next concept.

However, Hamilton says: “For us, we’re about excellent maths teaching. That’s what we’re about, and excellent teaching of anything to lead to mastery.”

And then there is Power Maths, which was developed by Pearson and designed to align with White Rose Maths. The textbook used in the programme has a Chinese co‑author and was judged to meet the requirements of the government textbook subsidy.

Simon Holden-White, product manager at Power Maths, makes it clear that its definition of mastery also comes from the NCETM’s work. The fully resourced curriculum programme, he says, gives teachers a framework of how to teach the five big ideas in the classroom. Yet he is also not particularly attached to the “mastery” label.

“We want to be consistent with what schools are being asked to do. At the top level, there’s an understanding about what we mean by ‘teaching for mastery’, and once you filter it down, people latch on to different things and talk about different things,” he says. “If a school is just interested in good maths teaching, there’s really no need for us to talk about ‘teaching for mastery’.”

Questions could be raised about how different these programmes are from the NCETM’s in reality - but, clearly, in emphasis and interpretations of mastery, there is variation between them.

What is also clear is that when all of these schemes hit the classroom, the variation becomes even more pronounced, both between schemes but also between schools.

Sarah Desborough is the headteacher at Cleobury Mortimer Primary School in Shropshire. She was in the first cohort of teachers to go through the NCETM’s TfM training, and has since trained others in the approach.

“The term ‘mastery’ is bandied around a lot, but I think there are subtle differences and sometimes quite big differences between what people’s understanding of the term is and what teaching for mastery looks like,” she says.

Camilla Pratt, a primary maths lecturer at Leeds Trinity University, is researching how varied those interpretations are.

Pratt’s analysis is ongoing, but so far she’s reporting differences around the use of mixed-ability groups, the use of equipment and the need to move on through the curriculum regardless of whether every child has fully mastered a concept.

Those differences are sometimes purposeful; schools are looking at the programmes and taking what they think is useful from each.

Jenny Laurie, head of maths at The St Marylebone CE School in London, says her department uses a combination of Complete Maths, White Rose and TfM.

Having options of programmes is helpful, she adds; teachers can pick and choose the elements they deem most appropriate, and it doesn’t matter if different schools teach maths differently.

“I’m sure each of the organisations would say you have to use its scheme in its entirety, but teachers are professionals - let’s treat them as such,” she says.

Get with the programme

Some argue that the inconsistencies in how mastery approaches are being interpreted and applied are problematic.

McCourt, for example, is firm: teachers should stick to just one programme.

“The Complete Mathematics curriculum is a carefully designed, coherent journey through the whole of school-level mathematics. This coherence is critical in a mastery approach,” he says.

“Breaking it means breaking the impact that mastery can have. This is why we suggest it is not possible to mix curriculum models.”

White Rose and Ark, however, seem happy for teachers to use their judgement on what works best for them, but do stress that solely following their approach would be the most effective way of teaching.

“Sometimes, teachers can have this tendency of moving and changing things, and at the end of the day it’s up to them. But if they follow White Rose Maths in the order it is meant to be done, it’s probably going to be more effective,” says Hamilton.

Drury, meanwhile, highlights the evidence of Ark’s impact, which suggests that teachers will achieve greater success if they complete Ark’s induction training, attend Ark’s conference and engage with the unit narratives.

“Ultimately, we just want to give teachers as much support as possible to do a great job. Where teachers are choosing to use elements of another programme, we tend to ask whether that means we should develop our programme to include that so that all our partner schools can benefit,” she says.

At the NCETM, Morgan believes that it’s right to give schools a choice about which programme they use, as long as “teachers plan and give lessons that stick to the underlying principles of mastery”.

So, where does all this leave schools? With so much variation, it’s difficult to know what works and what doesn’t - and whether a mixed approach is actually best. Boylan says the only way to find out is to do more research.

In his 2019 review of the TfM programme, he found that while “randomised controlled trials of mathematics mastery suggest potentially small benefits, and these are more likely at key stage 1”, “evaluations of the impact of adopting mastery teaching methods in England do not indicate the politicians’ hopes are likely to be realised”.

His conclusion stressed: “It is time for the government to take stock and to investigate in more depth which of the different practices they are putting forward under the mastery banner are most effective.”

Three years later, he points out, this still hasn’t happened.

“We don’t know if schools are better off using White Rose, Mathematics Mastery or Power Maths,” says Boylan. “We just don’t know. It’s good that individual organisations like the NCETM do their own evaluation, but they do not have the resources to assess the impact for pupils.”

More research is slowly emerging, though.

In 2014, the EEF published a review of Ark Mathematics Mastery, which found that key stage 1 pupils in schools adopting the programme made, on average, two months’ additional progress than pupils in comparison schools.

As a result, the EEF is funding a scale-up of the programme, helping to roll it out to more schools over the next two years.

There’s also research to come on the effectiveness of White Rose and Power Maths. The former has been evaluated by the EEF, with the report due out next year, and the latter has been analysed by UCL and a report is due to be published imminently. There is no research to come, as yet, on Complete Maths.

When asked if the NCETM would welcome a full-scale study on the impact of the TfM approach, Morgan replied “absolutely”, and said it was something the organisation would be “very positive about” - but made it clear it would be the DfE that would commission that research, rather than the NCETM itself.

The DfE, when asked, pointed to the recent positive review of Ark’s programme, which, it says, “draws on similar pedagogical principles to DfE’s own Teaching for Mastery programme”.

It also said that it is planning a new independent evaluation of the TfM maths hubs programme in the 2022-23 academic year.

‘A lot of teachers don’t know the best, most effective evidence-informed ways of teaching maths’

Will this research make a difference? Drury isn’t sure. She says it would be better to study the individual components of maths mastery approaches rather than the available programmes.

“We need a really good understanding, nationally, about what the evidence-informed approaches to curriculum design and teaching in maths are,” she says.

“In the past decade, we’ve got much clearer about that. However, there’s still a gap. A lot of teachers don’t know the best, most effective evidence-informed ways of teaching maths and, to some extent, it’s not helpful to compare the programmes, because teachers will always engage with schemes at different levels.”

An evaluation of the different components of mastery would be complicated to set up, Drury admits: it would need to compare schools and the elements of mastery they use, factoring in the teachers, the children, their home lives and the culture. But it would be worthwhile, she believes.

“All the providers could then make sure their programme only included the things we know make a difference,” she says.

In fact, researchers at the University of Cambridge have already started work in this area.

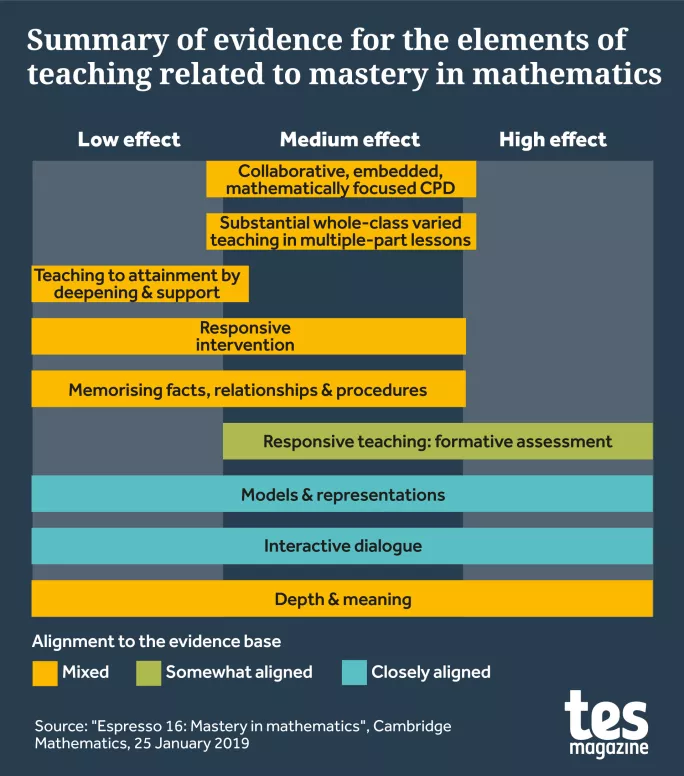

In 2019, they concluded that there are seven elements of teaching related to mastery in mathematics, and gave each one a different rating of effectiveness (see the diagram below).

A summary of this research, produced by Cambridge Mathematics, points out that as mastery has come to mean “multiple different things in research, practice and policy”, “looking at different aspects of ‘mastery’ separately rather than conflating them may be useful to teachers”.

For Watson, there is a clear need for more “sensible evaluations” like this.

However, she says, that doesn’t mean that the development of maths mastery in England has been a waste of time. All the programmes mentioned in this article are underpinned by the universal idea that all children are capable of succeeding in maths - and this, she says, is a massive sea change for maths education.

And there has been a positive effect for teachers, too, she adds: the focus on maths mastery has led to what is known as the “Hawthorne effect”.

“This is the idea that if somebody is paying attention to you, is interested in what you’re doing and is providing you with some training and support, you’ll do it better,” she explains. “In teaching, we want the Hawthorne effect. We want children to feel the teachers are interested in their learning. We want teachers to feel people are interested in their teaching.”

So, while we might not quite be there yet on a clear definition of maths mastery - and on the evidence base for how we apply that in UK classrooms - the current focus on maths pedagogy, and teacher development funding that comes with it, is not to be sniffed at.

Going forwards, then, the ideal scenario would perhaps be to maintain this focus and momentum while recognising that to learn more about good maths teaching, we might need to extend that focus beyond maths mastery.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article